Conditions I treat......... Developmental Hip Dysplasia

Developmental dysplasia of the hip, (almost) synonymous with congenital hip dysplasia and often simplified to hip dysplasia, is one of the most commonly treated leg conditions in Pediatric Orthopedics.

Hip dysplasia essentialy means that the socket of the hip joint is shallow. It is a spectrum condition with complete hip dislocation at birth existing as the most severe manifestation. Early diagnosis is crucial to optimise outcome. The earlier the diagnosis, the greater the chances of success with less invasive treatment methods and the better the outcome. Diagnosis may be shortly after birth on ultrasound assessment, at walking age as a late presentation or later in adult life when mild hip dysplasia becomes symptomatic.

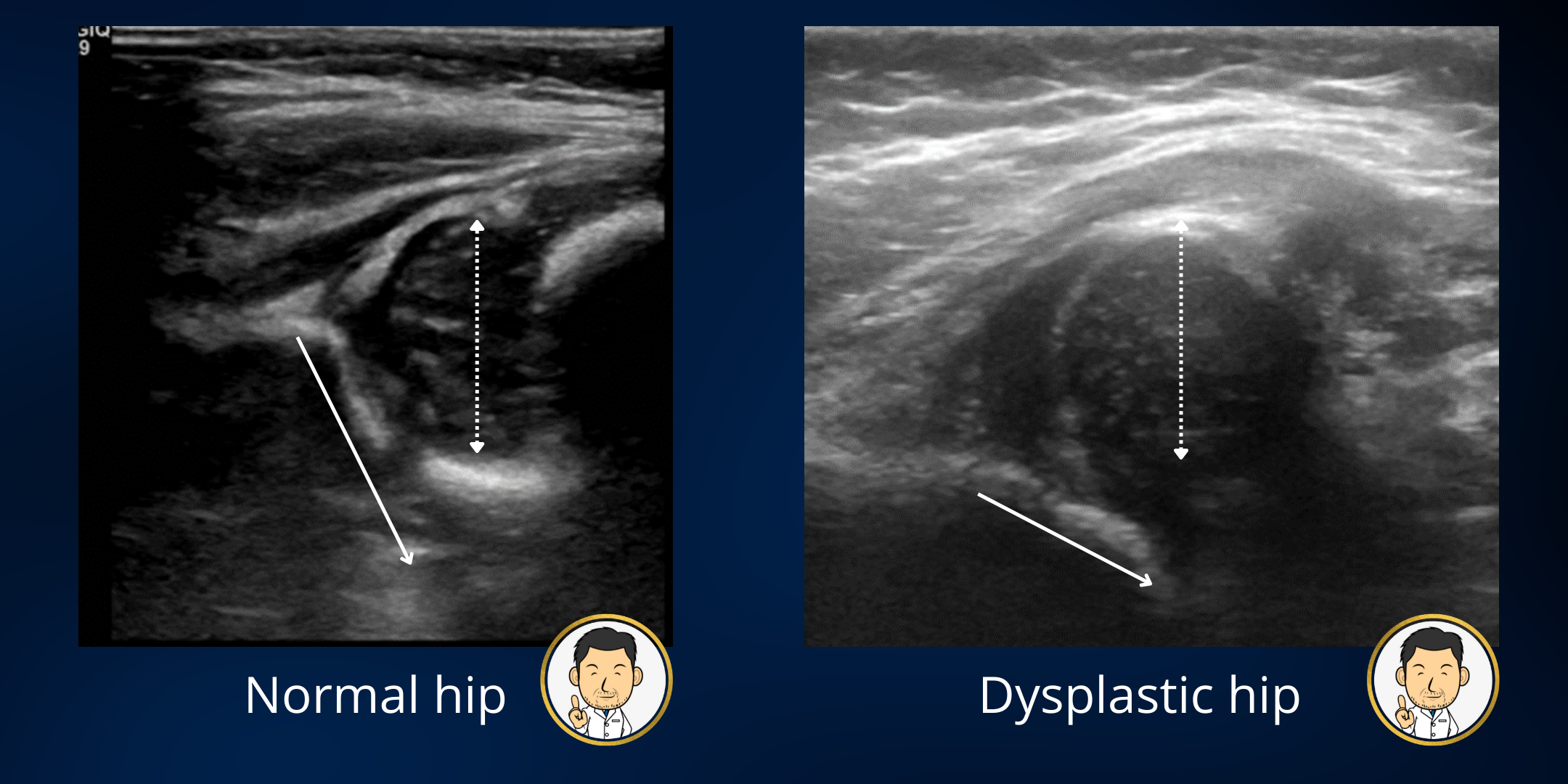

Neonatal hip ultrasound diagnosis

Ultrasound of a baby's hips is the best clincial tool we have for detecting hip dysplasia early. Although a few countries practice universal ultrasound screening of all newborn babies' hips, most countries adopt selective screening based on the presence of risk factors for hip dysplasia. The main risk factors are a family history of hip dysplasia amongst first degree relatives and breech lie towards the end of pregnancy. Hip sonographers are usually the best operators for undertaking hip ultrasound assessment in newborns. The sonographer will usually scan the baby on their side, scanning each hip in turn. They will save an image of each hip in a defined plane, assess stability and measure the Alpha angle (used to define a threshold for treatment with <60 degrees viewed as abnormal). They will also usually measure the Beta angle (usually because the automated software prompts this even though most evidence suggests it contributes little to management). Alpha angle and stability are the key assessments on which a decision to treat is based.

If the scan is normal (normal alpha angle and stable), the baby will often be discharged. However, if the scan is abnormal, the baby will be referred to a Pediatric Orthopedic Surgeon with the saved ultrasound images. Many clinics work with the Pediatric Orthopedic Consultant not being present for the scan. They will often read the report and view the static images to make a decision on treatment. Clinical examination in isolation has been shown to be thoroughly unreliable (in most studies all the way up to the present - it seems like we haven't become much better at examination over time). As clinicians, we are very much reliant on the scan to tell us what is going on in the hip rather than what we feel when we examine the baby. The question then arises as to when to treat? What if the alpha is 58 degrees but the hip is stable? Do we need to treat?

The question of whether a reduced alpha angle is sufficiently abnormal to merit treatment is best undertaken by a Pediatric Orthopedic Consultant viewing the ultrasound images in realtime. Ultrasound assessment undertaken in the first few days of life (especially in premature births) frequently over-diagnoses hip dysplasia. The reason is that in hips that are stable, the alpha angle usually improves in the weeks following birth (this is the basis for the recommendation of scanning hips between 4-6 weeks if they feel stable on clinical examination).

Reviewing saved static images alongside measured angles makes treatment thresholds difficult. Should you treat an alpha angle 2 degrees off from normal if the hip is stable? If you are not present for the scan you may be worried that there is some instability. Often ultrasound findings are more likely to lead to over-treatment than under-treatment. A helpful adage my colleague came up with to justify sitting with the sonographer to interpret the scan in real time - "when scanning a baby's hips, a good hip can look bad depending on the plane in which the hip is scanned, but a bad hip, can never look good no matter which plane the hip is scanned in."

Based on my training and personal experience, the combined hip ultrasound clinic is the best model of care. In a combined clinic, the sonographer scans the babies hips while the orthopedic surgeon reviews the images in real time. I feel that this is the gold standard in treatment decision making. I can see the dynamic images like a video reel. If there is instability as the baby moves their leg - the ball characteristically "bobs" in the joint rather than "rolls". If the image looks like the hip is shallow with less coverage, I ask the sonographer to re-scan to find the optimal plane for assessment of socket shape and depth. In this way, I hope that I will only treat hips that actually need treatment rather than those that will improve of their own accord.

Pavlik harness treatment

Pavlik harnesses are "dynamic flexion abduction orthoses." In essence, they encourage the baby's hips to be positioned outward at rest whilst permitting some movement. They are low profile and babies will sleep comfortably in them. Nonetheless, as new parents, any barrier between skin contact feels intrusive and parents can often become tearful as treatment is explained (which is why I really try to only treat hips that need a harness).

The pavlik harnesses are usually applied and fitted by our specialised Pediatric Orthotist and then checked by myself. We mark the straps so that parents know the settings. I recommend 23 hours a day (off for 1 hour for bath and stretch) until the next visit. Appropriate sizing of the harness, adjustment of straps and looking for any complications is undertaken at each visit - frequency very much based on ultrasound findings and response to treatment. Crucially the decision of when to treat and for how long is undertaken by the Consultant Pediatric Consultant based on ultrasound monitoring of the hips to determine their responsiveness to treatment.

Athrogram assessment and attempted closed reduction in hip dislocation presenting early

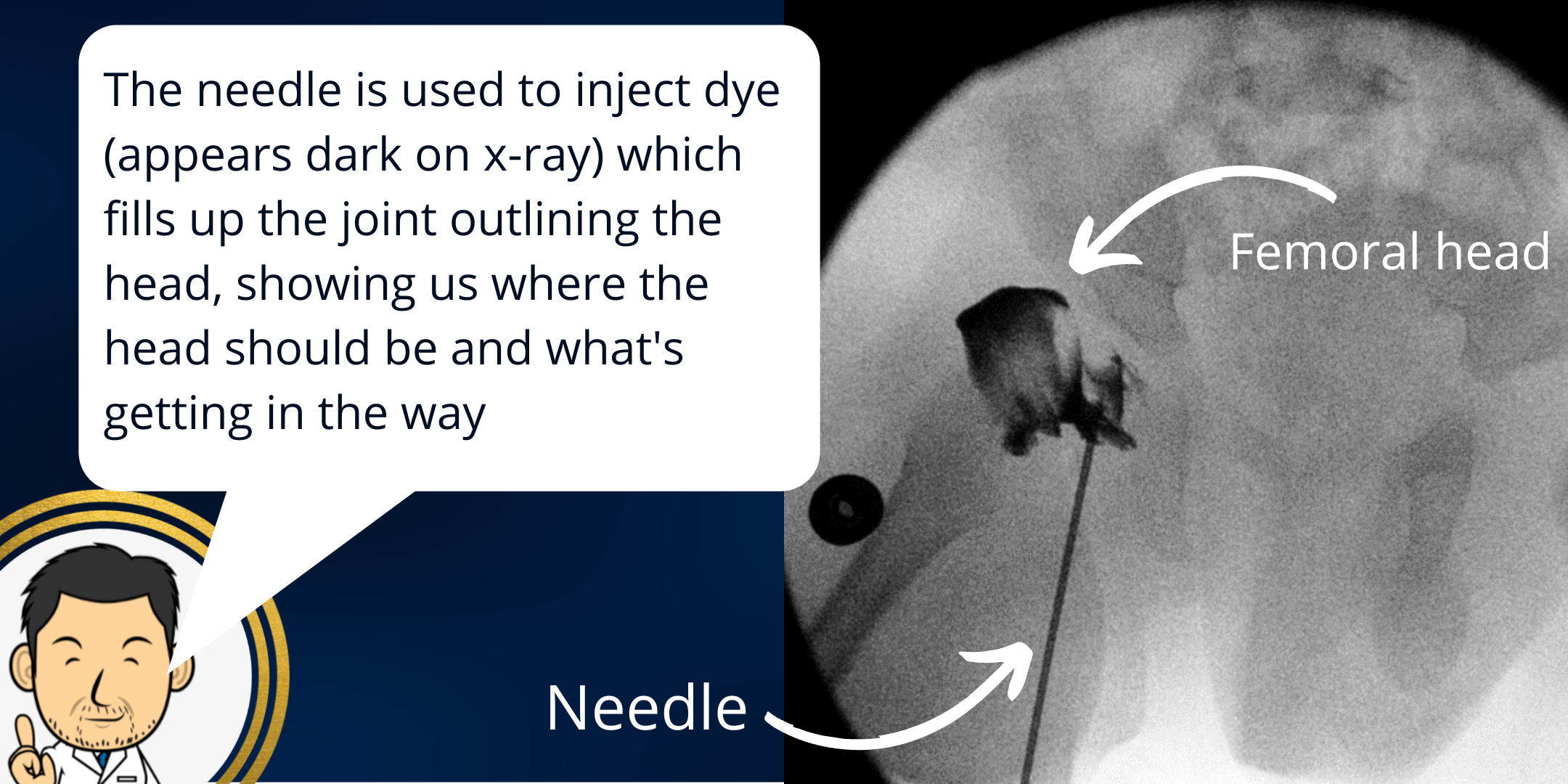

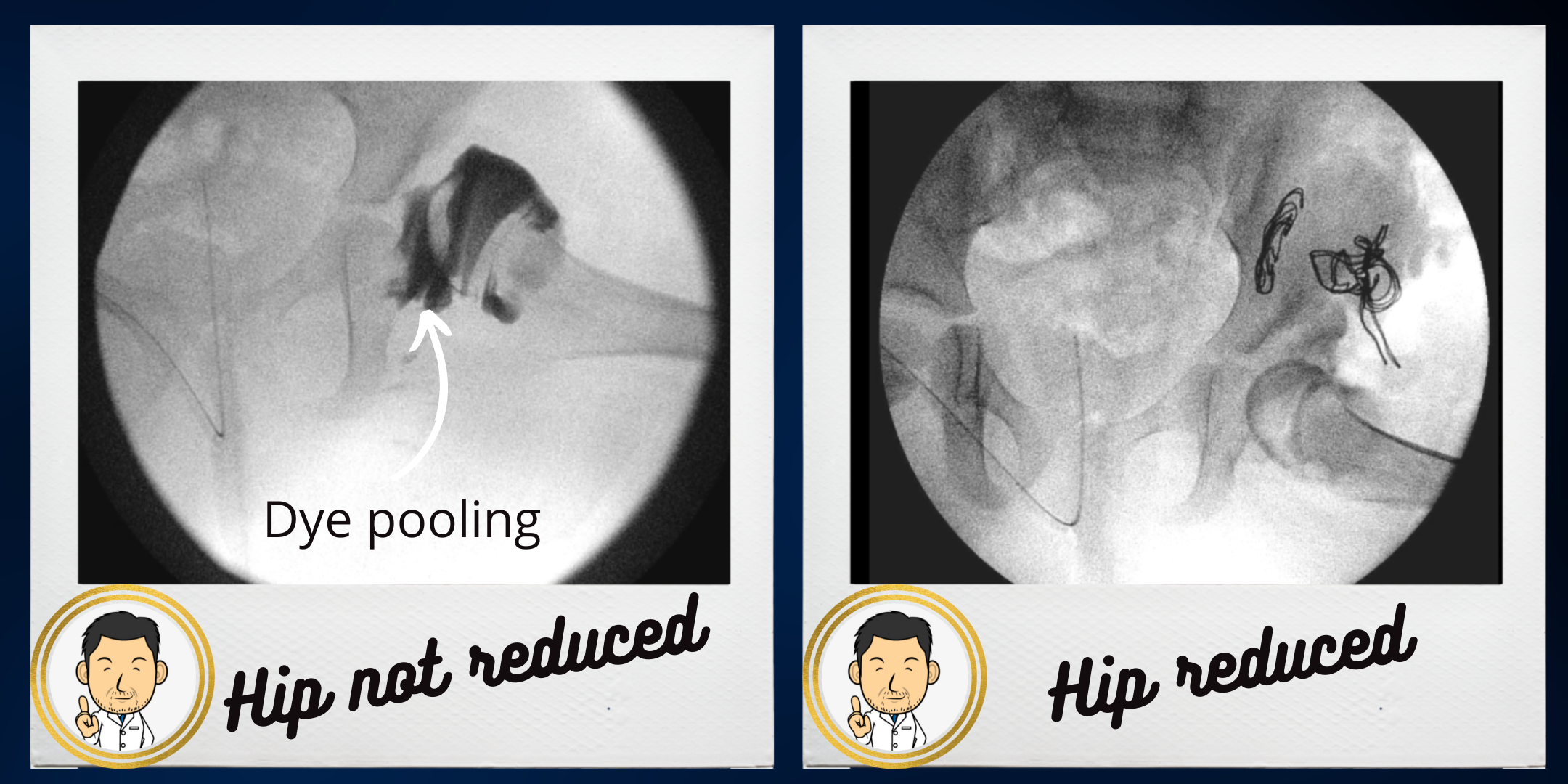

Unfortunately, not all hips respond to Pavlik harness treatment. If this is the case, I discontinue treatment as there is a risk of damaging the femoral head through prolonged use of a harness in a persistently dislocated hip. In such cases I would advocate arthrographic (dye injection) assessment of the hip under general anaesthetic when the child is a little older. I am a big believer in arthrographic assessment in hip dysplasia to guide treatment. The injection of contrast in the hip enables appropriate visualisation of the femoral head (usually the cartilaginous femoral head is invisible on x-ray). Once the head is visualised, we can determine where it is in relation to the socket and how easily and satisfactorily it can be placed in the socket.

Performing an arthrogram has many diagnostic benefits. I use it to:

- Determine if the hip can be reduced "closed" (i.e. without surgically "opening" the hip) - if so, then the hip can be immobilised in a plaster cast (hip spica) to see if it will stabilise (usually 6 weeks is sufficient).

- How stable the hip is when reduced and the likelihood of repeat dislocation if treated in a hip spica - sometimes the hip does go back into joint but just as easily pops out. In this instance a hip spica cast is unlikely to be effective.

- Elucidating the physical barriers preventing a hip from succesfully reducing (planning for what to do next)

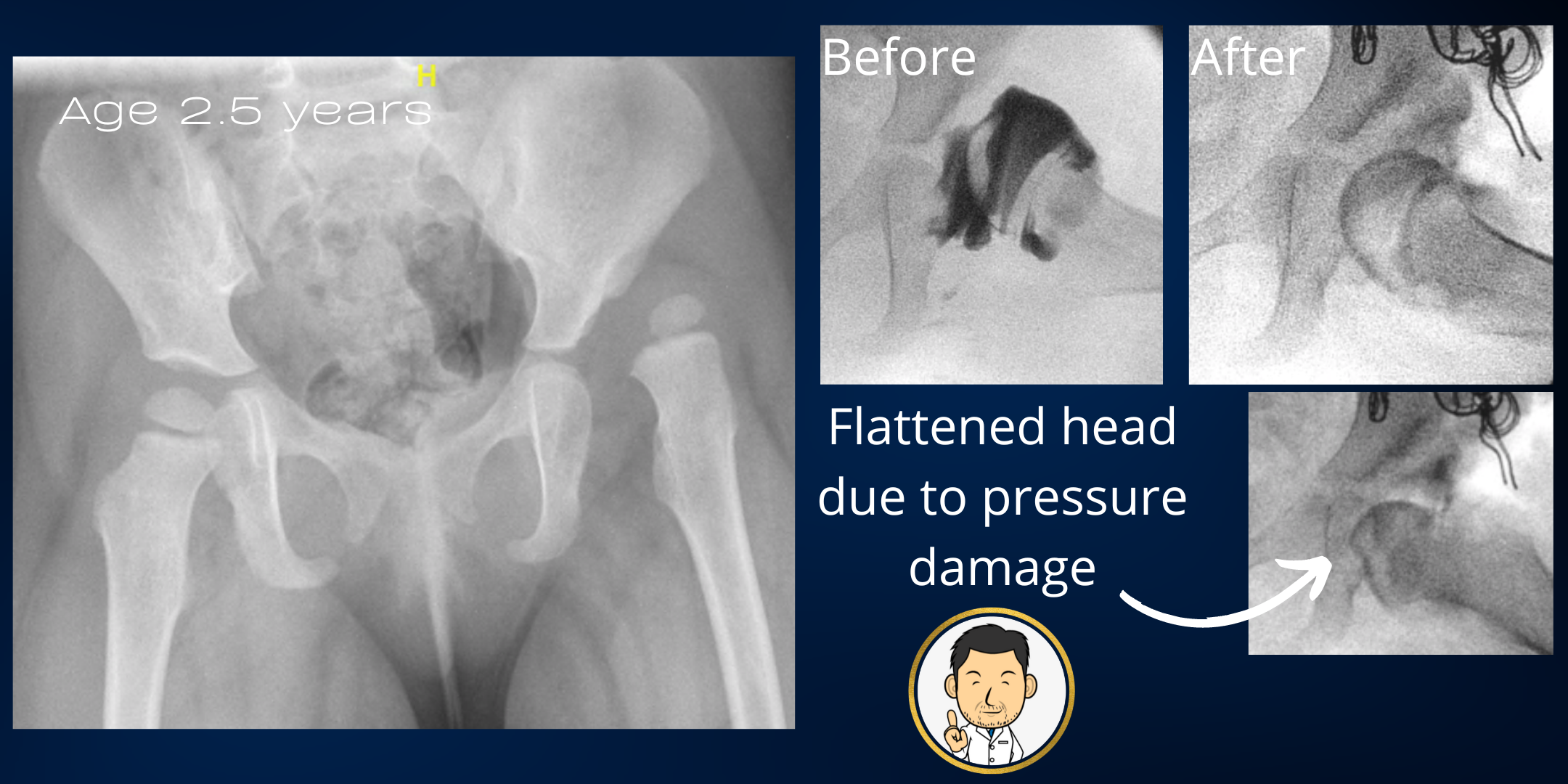

Not every dislocated or dislocatable hip needs open surgery as hips that do reduce easily and are stable on arthrogram may just need a plaster cast for 6 weeks. However, a hip should never be forced into the joint under pressure and placed into a cast. This risks the most feared complication - avascular necrosis of the femoral head (or "proximal femoral growth disturbance" as described in more recent times). In this complication, the femoral head is injured (likely relating to pressure induced damage from being placed in the joint) with subsequent development of an abnormally shaped head (frequently squashed mushroom like appearence) which is difficult to reverse.

Surgery for hip dysplasia

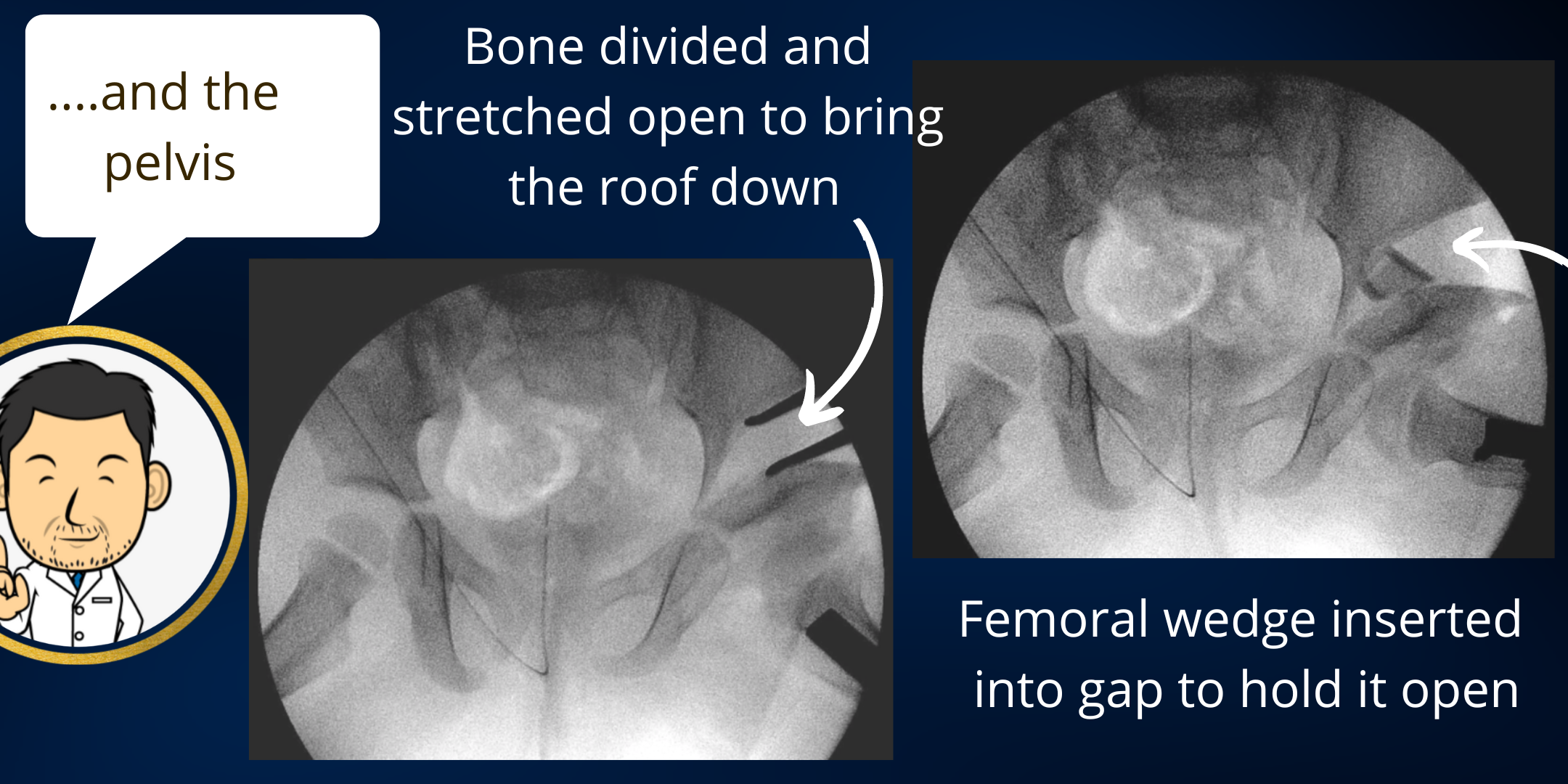

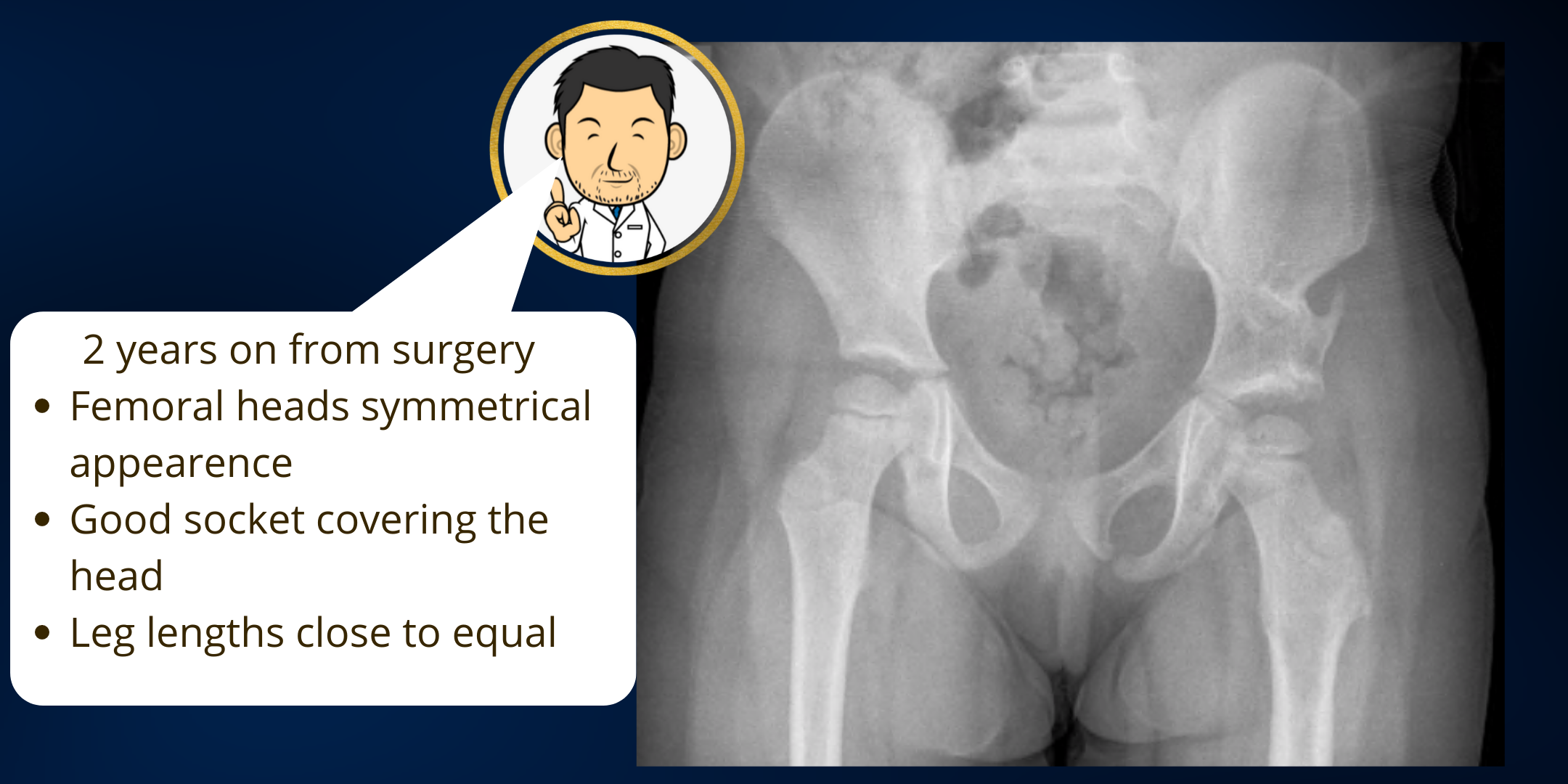

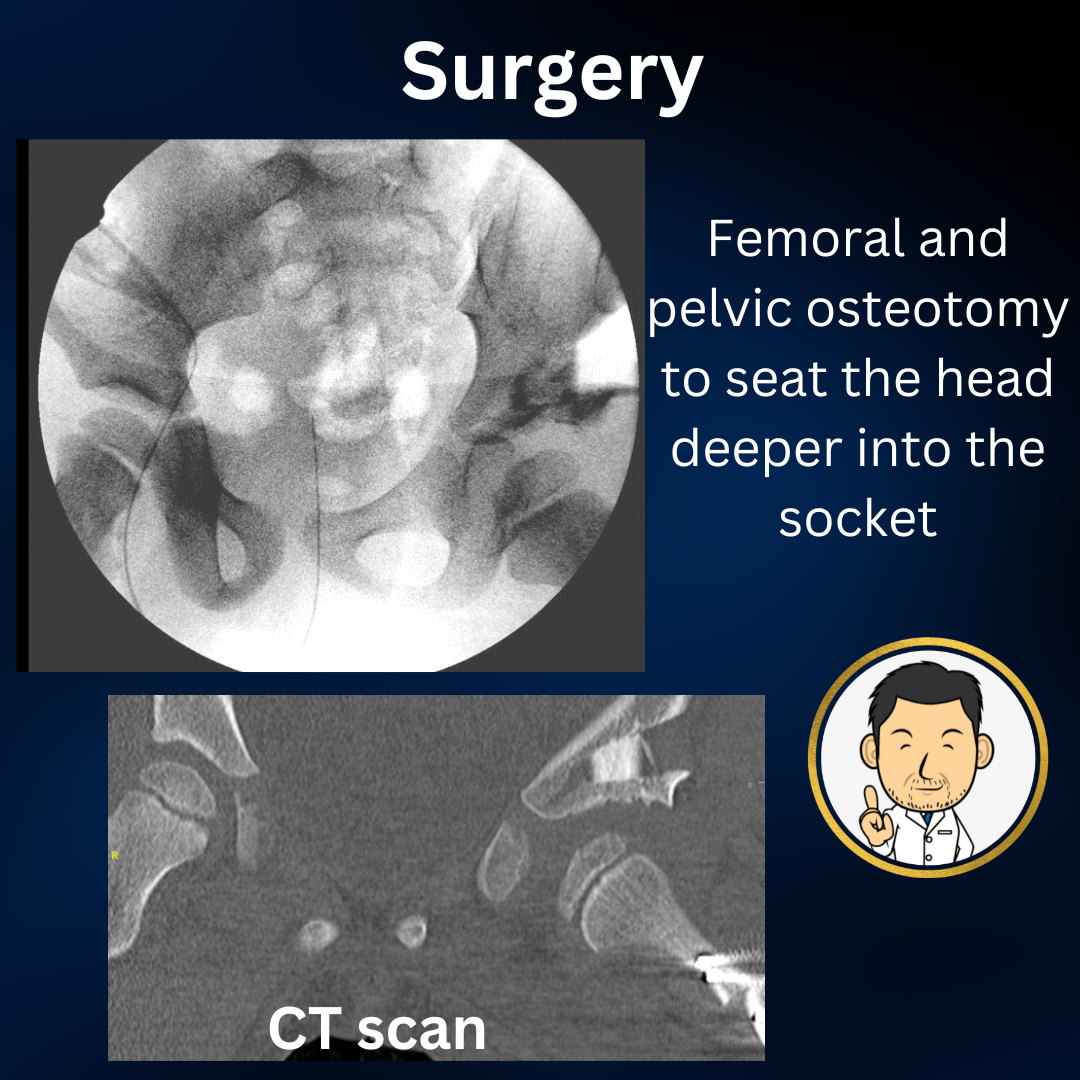

Single stage hip reconstruction for late presenting hip dislocation in children of walking age

In cases where the hip will not re-locate by closed means, often in an older child, this comprehensive surgical approach is aimed at reducing the hip back into the joint so that it is in deep and stable (usually confirmed with an arthrogram). It is combined with a femoral and pelvic osteotomy (bony surgery) to correct all associated deformities and minimise the need for further procedures when the child is older. Many surgeons may adopt a different approach choosing to perform an open reduction alone and then undertake further surgery in the future as required. They may need to keep the child immobilised in a brace for several months following surgery while the socket depth slowly improves. Future surgery if required to deepen the socket can lead to multiple operations throughout the childhood of the patient. Dysplasia (socket shallowness) is often more challenging to treat as the deformity becomes more established as the child grows older.

In my practice I have found that there are several advantages to undertaking a comprehensive single stage hip reconstruction in preference to open reduction alone:

- Addressing the socket shallowness with a pelvic osteotomy provides sufficient stability to the hip so that only 6 weeks in a hip spica is required post-operatively with no bracing thereafter. Which is great for getting a child back to walking soon.

- Improving the coverage with a pelvic osteotomy is vital to stabilising the hip. I feel that a well done pelvic osteotomy is crucial to preventing re-dislocation of the hip following surgery. In the literature, the rate of re-dislocation is 8 to 20% and most surgeons would agree an acceptable risk is 10%. I am very grateful to God that my re-dislocation rate is far far far below this.

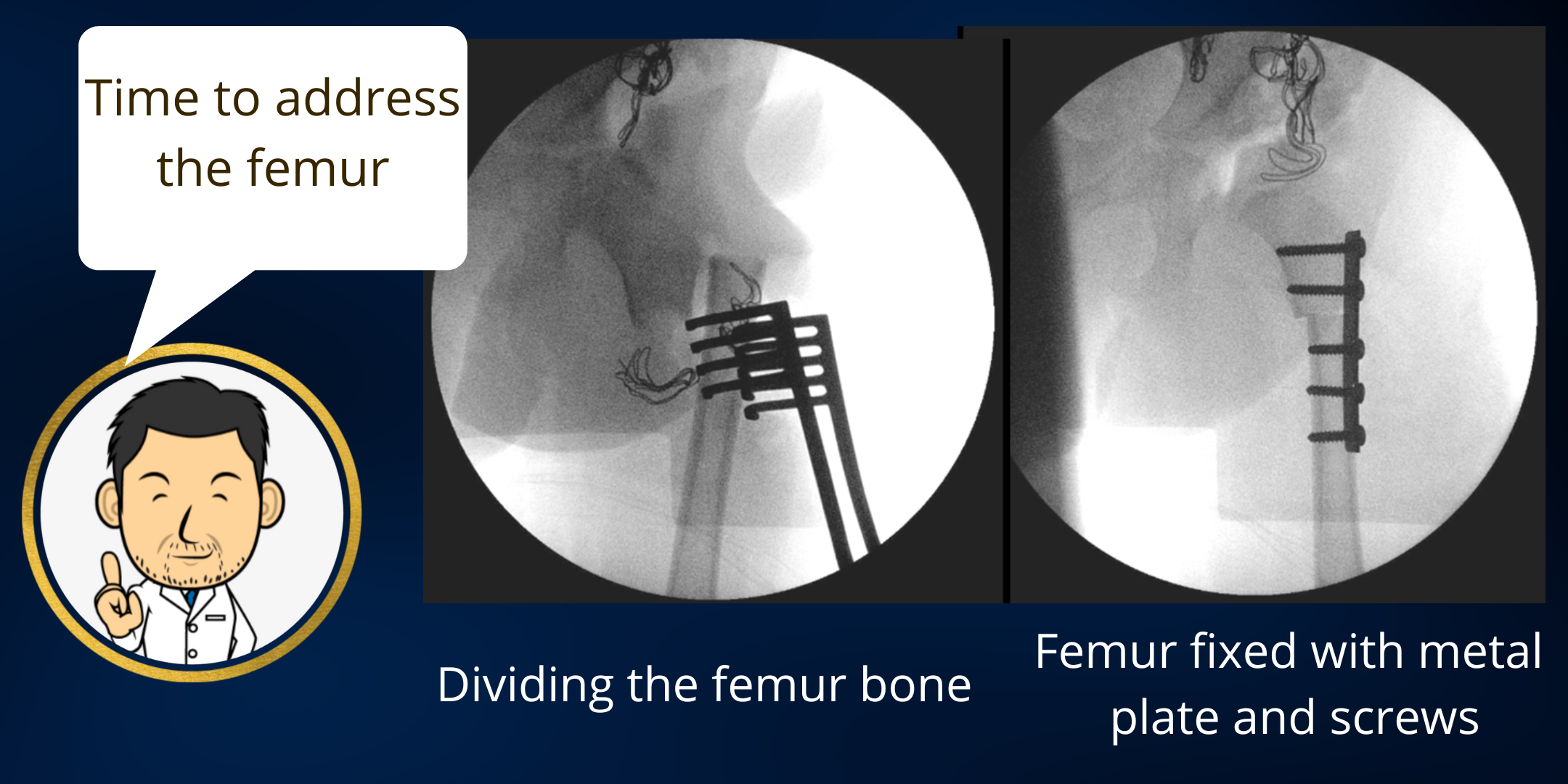

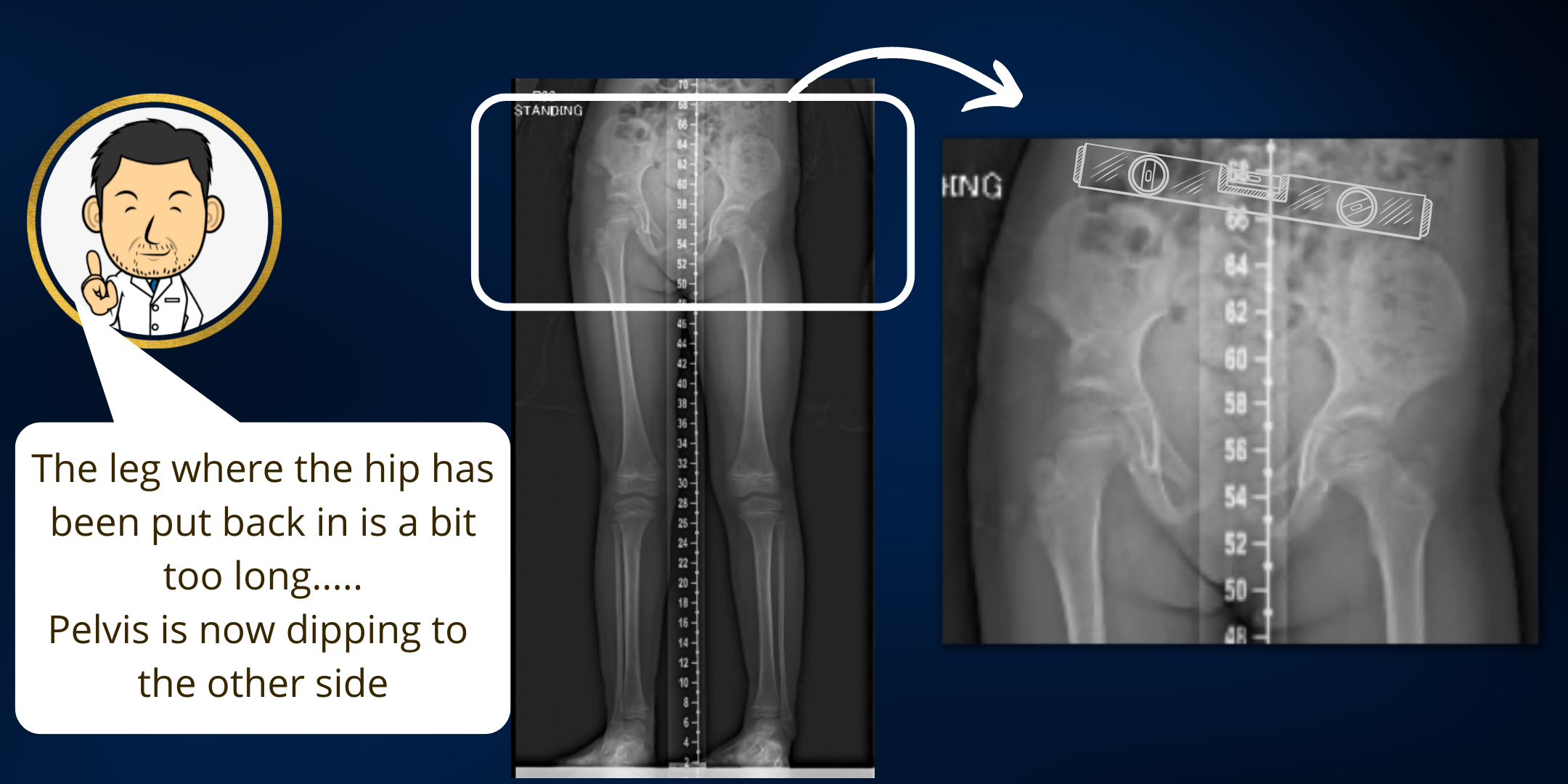

- Although not appreciated by many, the femoral length in a dislocated hip is usually longer than the other side. Undertaking a shortening femoral osteotomy is intended to equalise leg lengths when the child is older. Leaving the leg longer where the hip is shallow leads to further uncovering of the femoral head as the pelvis is tipped over to the other side in a standing position.

- Shortening the femur crucially detensions the surrounding muscles hopefully minimising the risk of avascular necrosis (femoral head damage) due to pressure on the head. A "tension free" reduction of the hip is an important technical objective.

- The rotational alignment of the femur can also be corrected so that the child's feet point in the same direction when walking.

- Single stage hip reconstruction hopes to minimise the need for further corrective surgery in the future rather than hoping for natural resolution of the associated deformities once the hip is put back in. The older the child when the dislocation is picked up, the greater the amount of "normal hip developmental time" that has been lost while the hip has been dislocated. If only an open reduction has been done, often the acetabular dysplasia (socket shallowness) fails to fully correct over time necessitating a pelvic osteotomy and/or a femoral osteotomy at a later stage. This often requires a further period of hip spica immobilisation. The expectation of several surgeries over a patient's childhood is a significant burden to both the child and the parents. It is one we are trying to avoid by undertaking comprehensive deformity correction in addition to the open hip reduction as a single procedure.

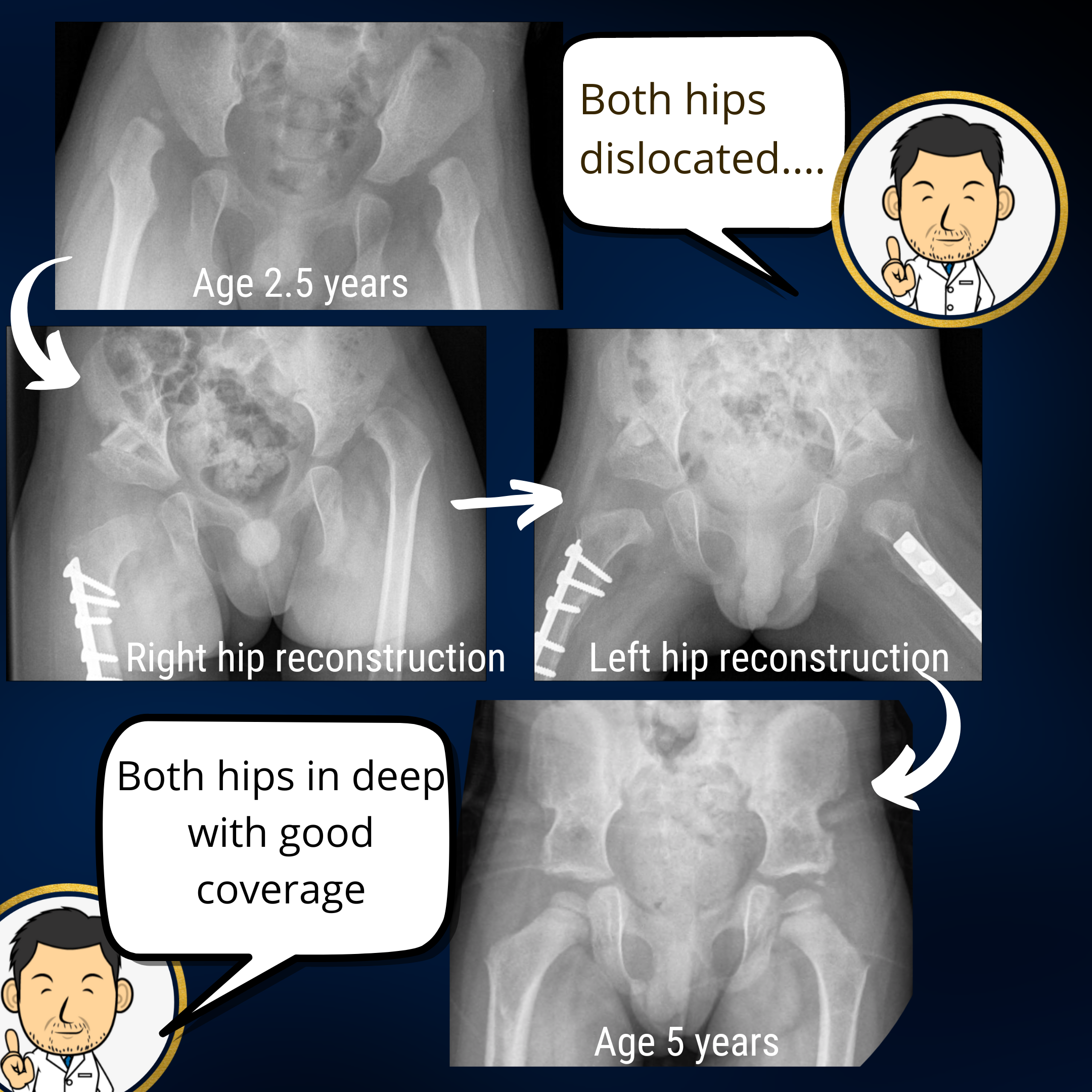

Bilateral hip dislocation

This situation is a little more tricky with both hips dislocated. Nonetheless, I will always start out with an arthrogram to see if both hips can be reduced (placed back into the joint) and are stable. If one of the hips is unsatisfactory in either regard (i.e. doesn't reduce or is unstable after reduction) then the closed reduction is abandoned in favour of open reduction with femoral and pelvic osteotomies. I do one hip first (usually the more unstable/displaced of the two) and then place the child into spica for 4-6 weeks before doing the same surgery for the other hip, and then back into spica for a further 6 weeks. Doing both hips at the same time with femoral and pelvic osteotomies is a bit much for a young child under 3 years of age in one sitting. Some surgeons get around this by doing an open reduction alone on both sides in one sitting but without the femoral or pelvic osteotomies. My concern with this is that the deformity correction with the osteotomies is crucial for stability. When both hips are dislocated there is a significant risk of re-dislocation for at least one of the hips. In children over the age of 5 years undertaking surgery on both hips at the same time with two surgical teams is more feasible.

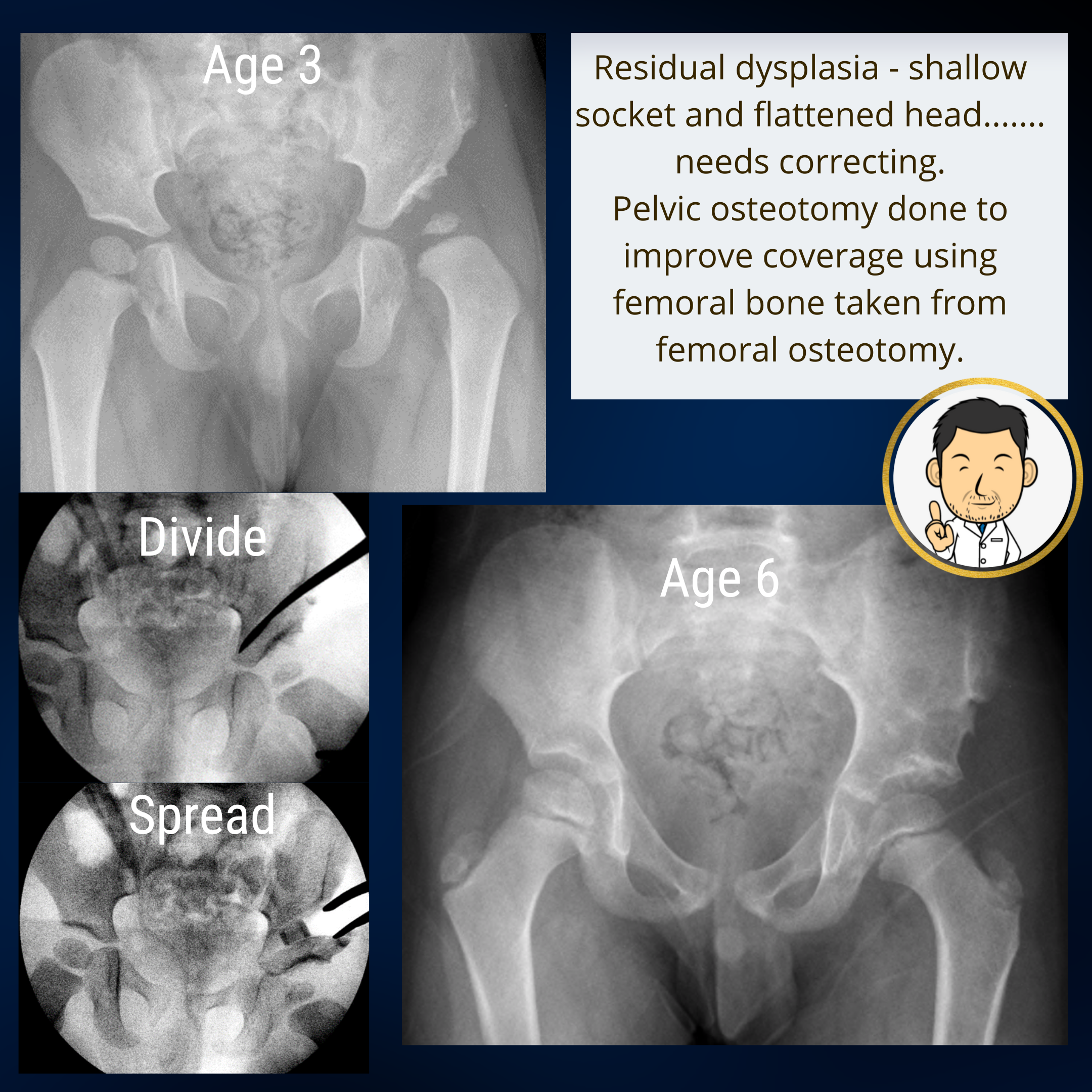

Surgery for residual dysplasia

I have treated several children who have had surgery with an open reduction undertaken elsewhere but the socket shallowness has failed to resolve. The mainstay of treatment here is femoral and pelvic osteotomies to correct the deformities without opening the hip joint. If the arthrogram suggests the hip can be reduced fully then I do not repeat the open reduction. I usually try to treat residual dysplasia before the age of 5 years for the following reasons:

- By age 4-5 years, serial assessment with radiogaphs has usually made it clear whether the hip has normalised sufficiently or whether it will remain shallow into adult life

- Surgery before the child starts regular school is preferable.

- A child can still be easily managed in a spica plaster cast without too much difficulty under the age of 5 years.

The big issue with residual dysplasia is the dichotomy between having a happy child running around in clinic but the doctor is telling you that things don't look great on the x-ray. Often, Pediatric orthopedic surgeons are overly optimistic about residual dysplasia resolving with further growth. The problem is that if left untreated, residual dysplasia often manifests in late childhood or early adolescence where symptoms and treatment can have a greater impact on education. Also, hip dysplasia in older children and teenagers is often more difficult to correct and requires more invasive surgery with longer recovery times.

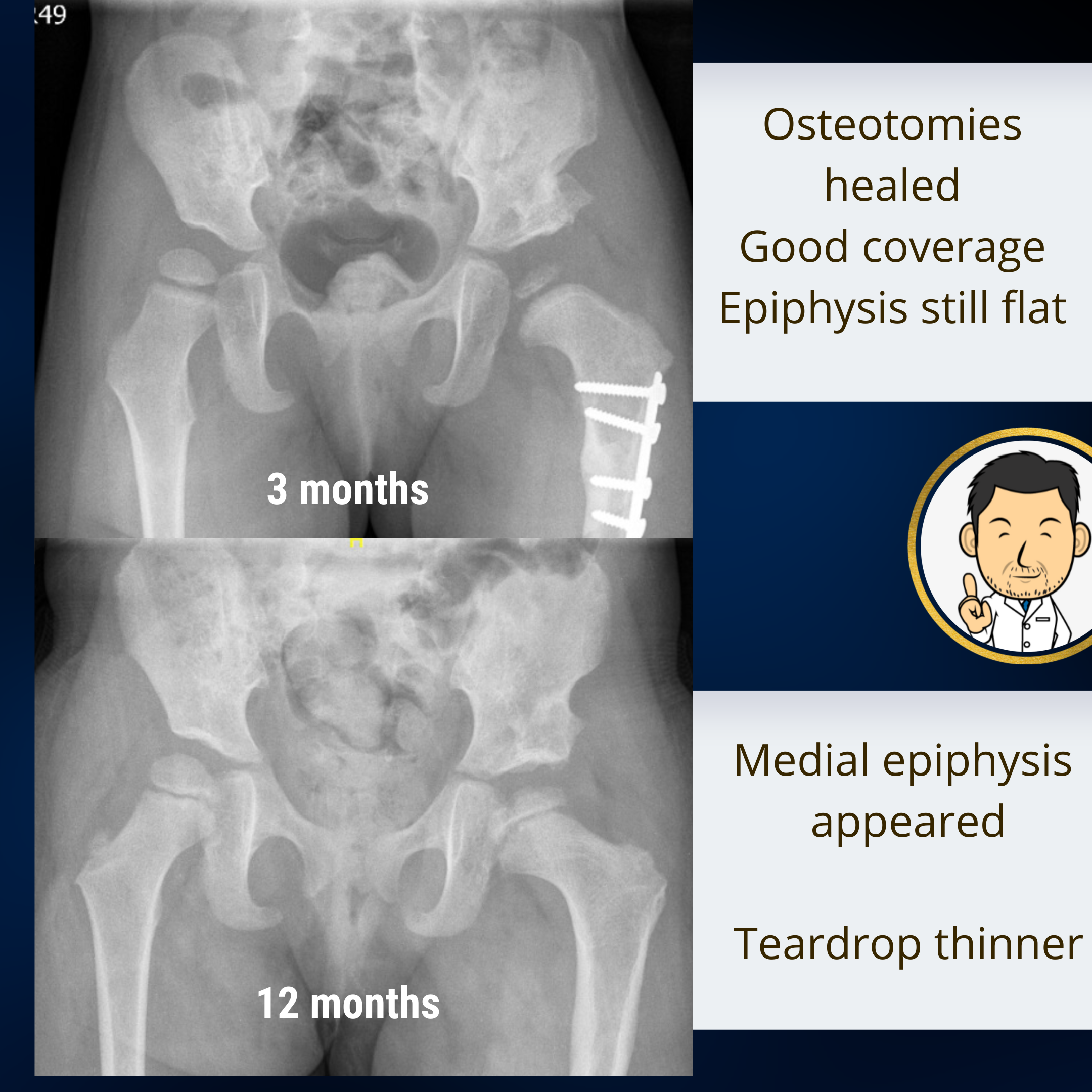

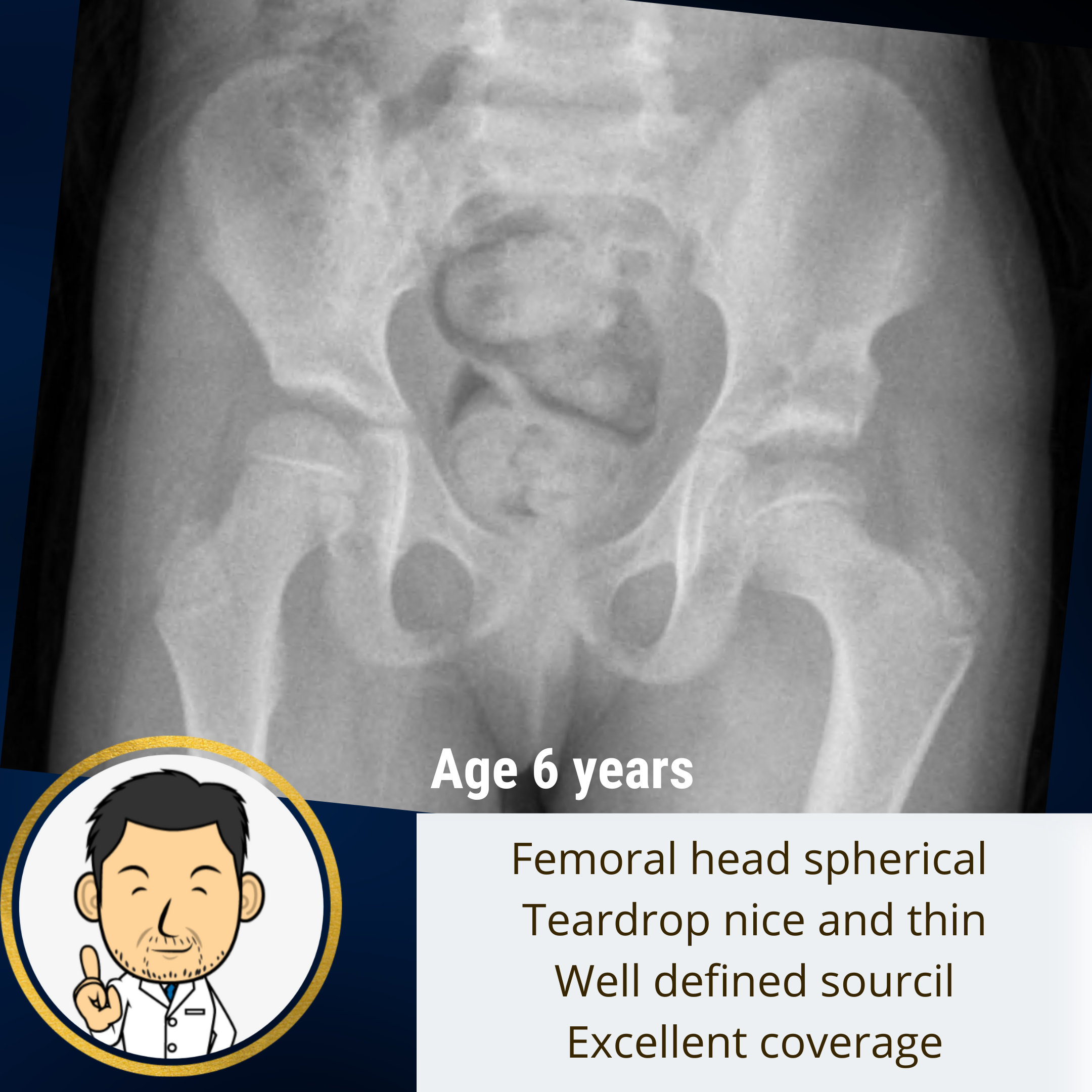

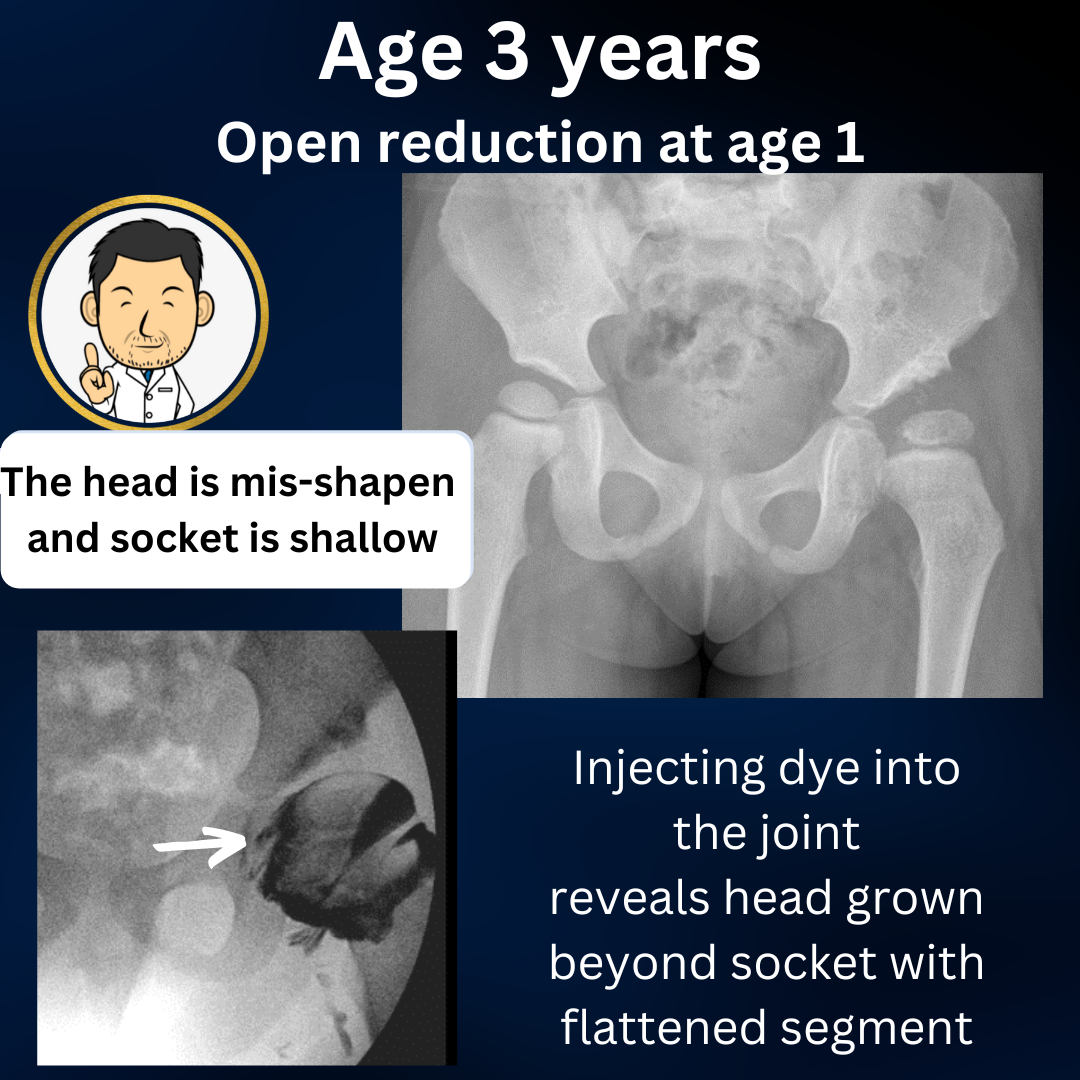

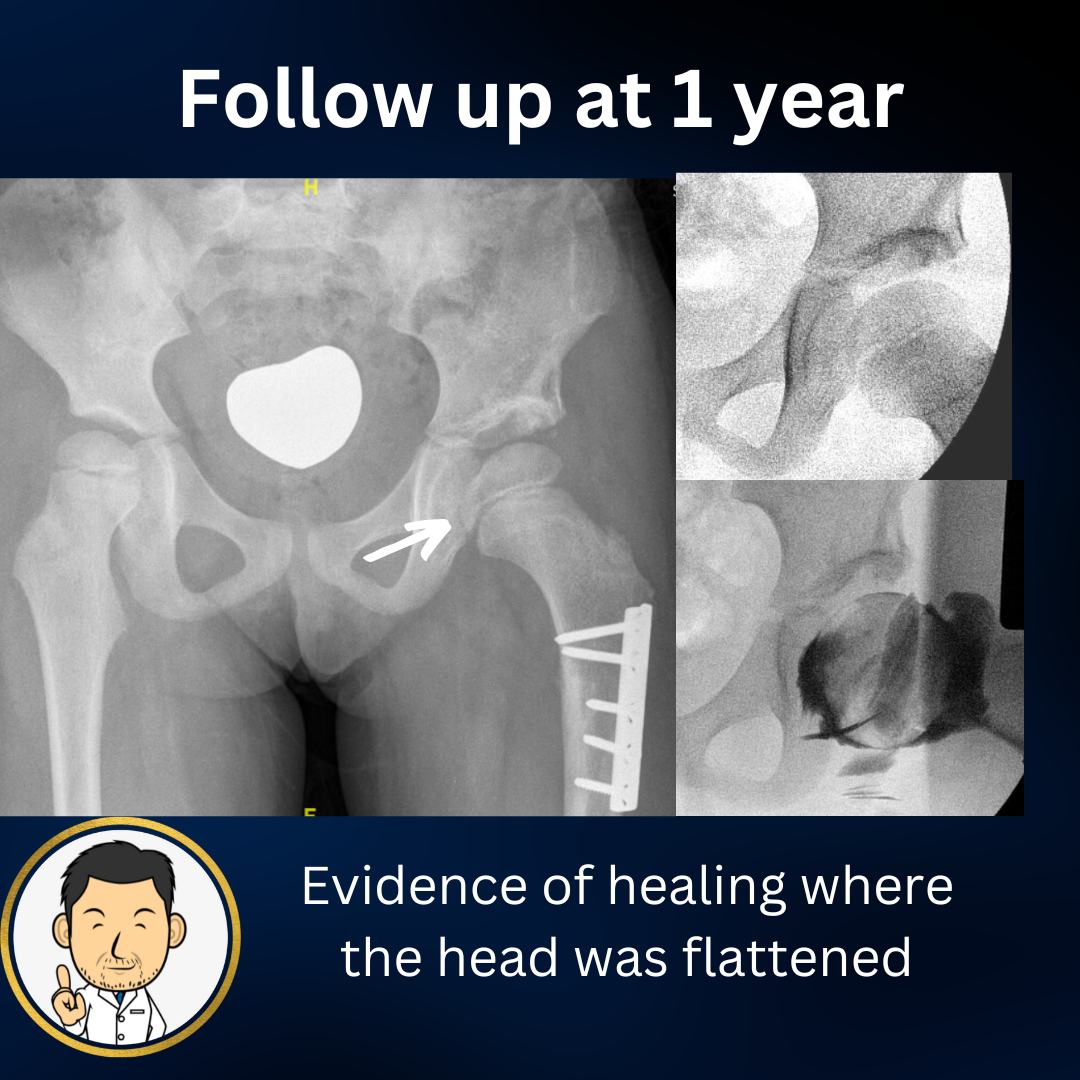

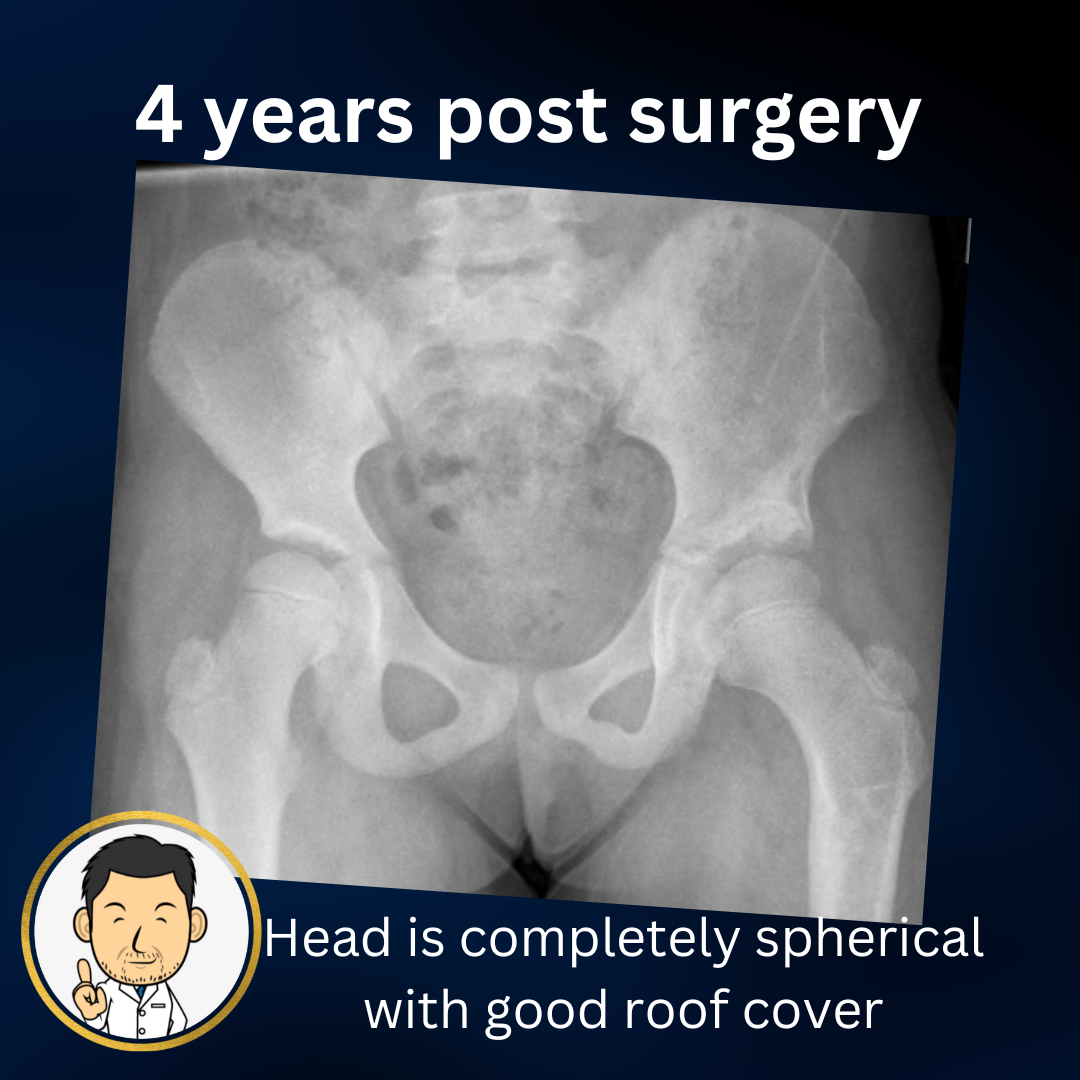

If there is sufficient evidence that the hip is not progressing in the right direction, then earlier intervention is better for the child. If the parents are sceptical, I will suggest that we do an arthrographic evaluation to denote the extent of the problem before progressing to surgery. Arthrograms are a good means of elucidating the distorted anatomy to parents and makes both parties more confident that surgical correction is indicated. Achieving earlier normalisation of the anatomy while remaining years of growth are on your side is a logical benefit to treating early. Proximal femoral growth disturbance (a better term for AVN head damage) is often associated with residual dysplasia. Free of the constraint of a well developed socket, the femoral head usually enlarges and develops a characteristic lateral bump over time. If residual dysplasia is corrected early, progression in these changes can be prevented and the head can heal into a more spherical shape. Let's look at a case.....

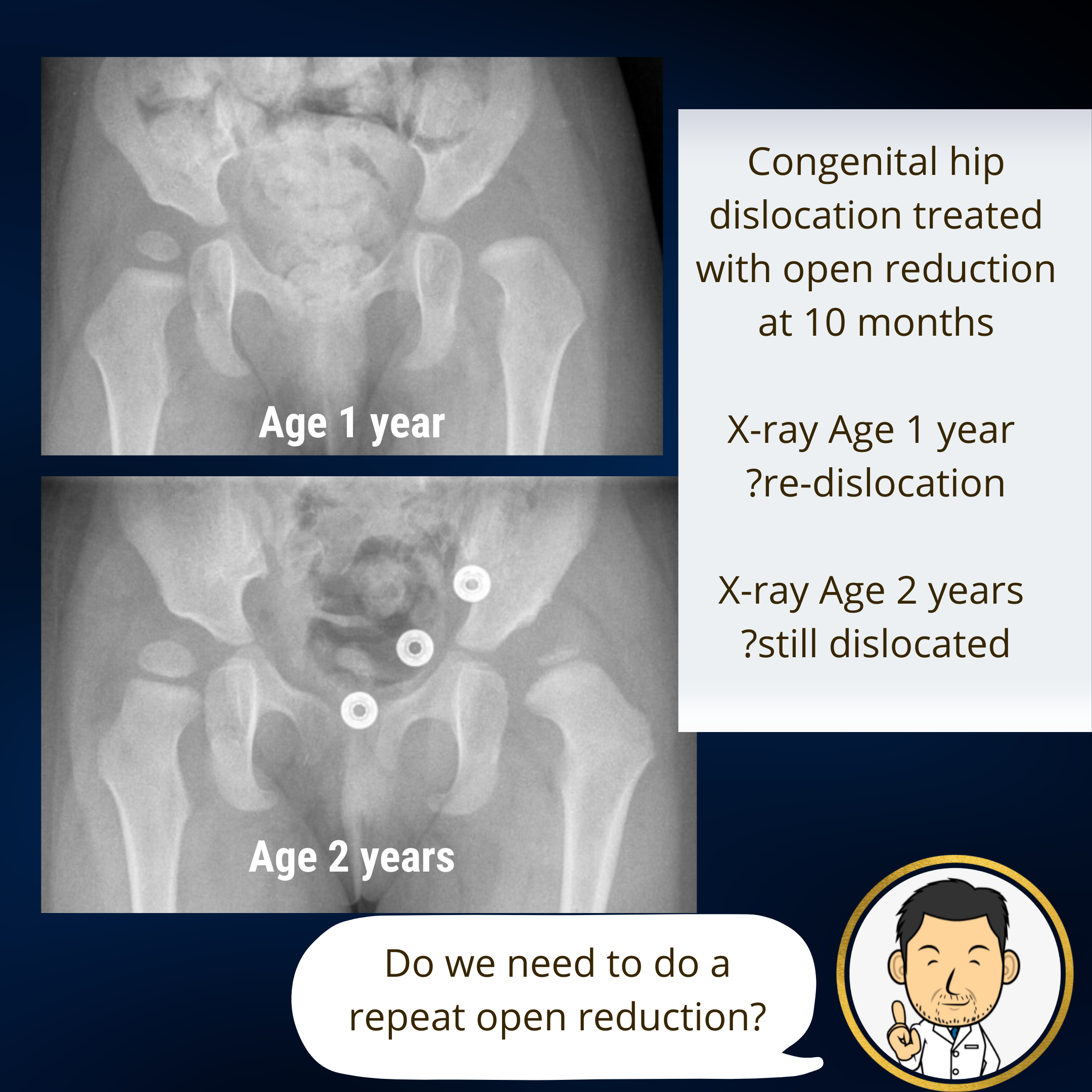

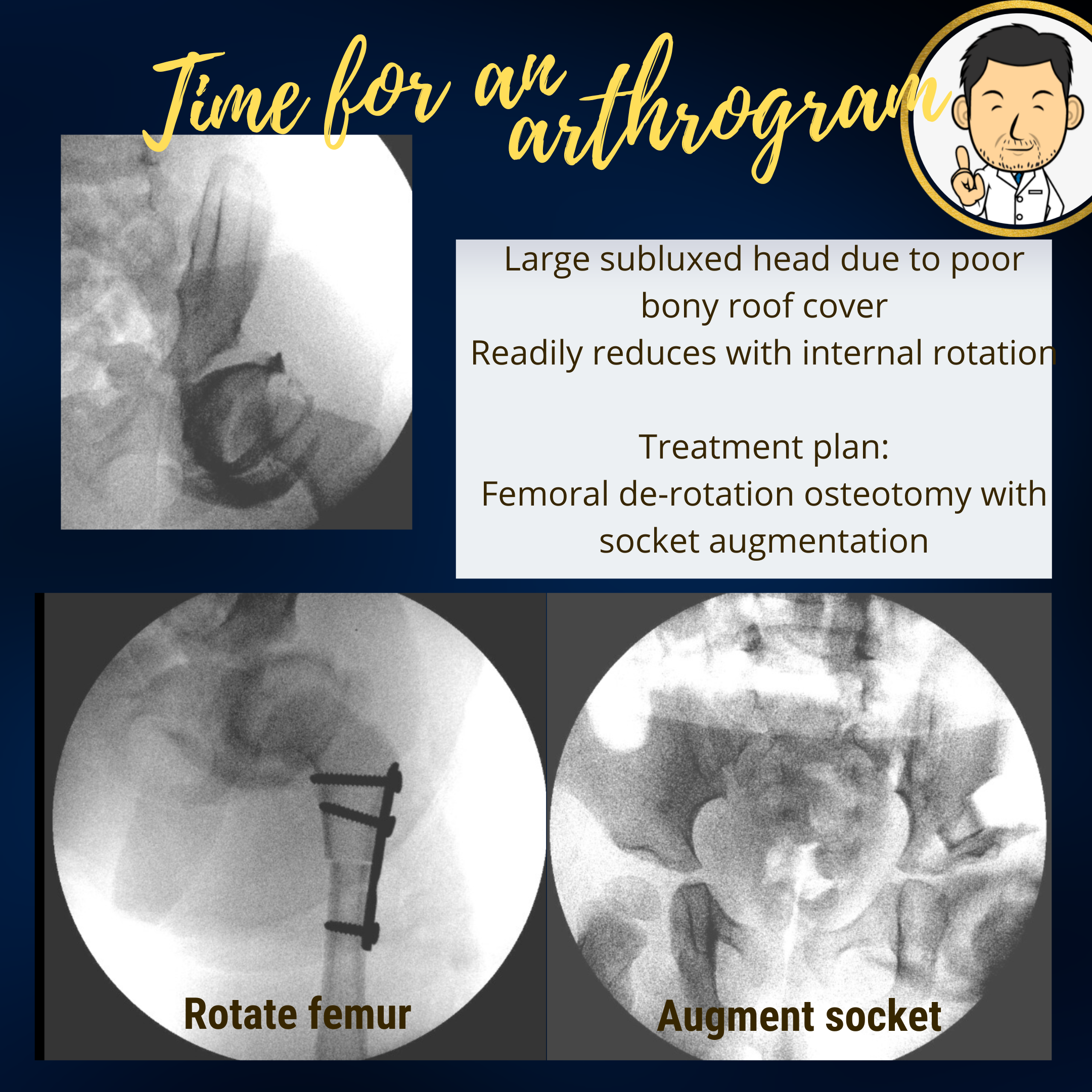

Revision surgery following hip re-dislocation

This is a very unfortunate scenario where surgery has been undertaken but the hip has re-dislocated. Often the causative factor is that the shallow socket was not addressed at the first surgery causing the hip to slowly slip out. These can be challenging cases but if recognised early enough, arthrogram assessment can be used to determine a patient specific surgical solution. If the hip reduces on arthrogram then there are no barriers to reduction. In this instance a pelvic osteotomy combined with femoral osteotomy can correct the deformities which are giving rise to the hip being unstable.

In certain cases, the hip has not actually re-dislocated after surgery. The hip is out because the first surgery did not achieve a satisfactory reduction due to persisting barriers (tight capsule, interposed structures). In this instance, as well as addressing the deformities in the femur and pelvic bones, the hip joint also needs to be opened to ensure a deep reduction. This does alter the risk profile so getting it right first time is very important.