Conditions I treat......... Hip reconstruction in Cerebral Palsy

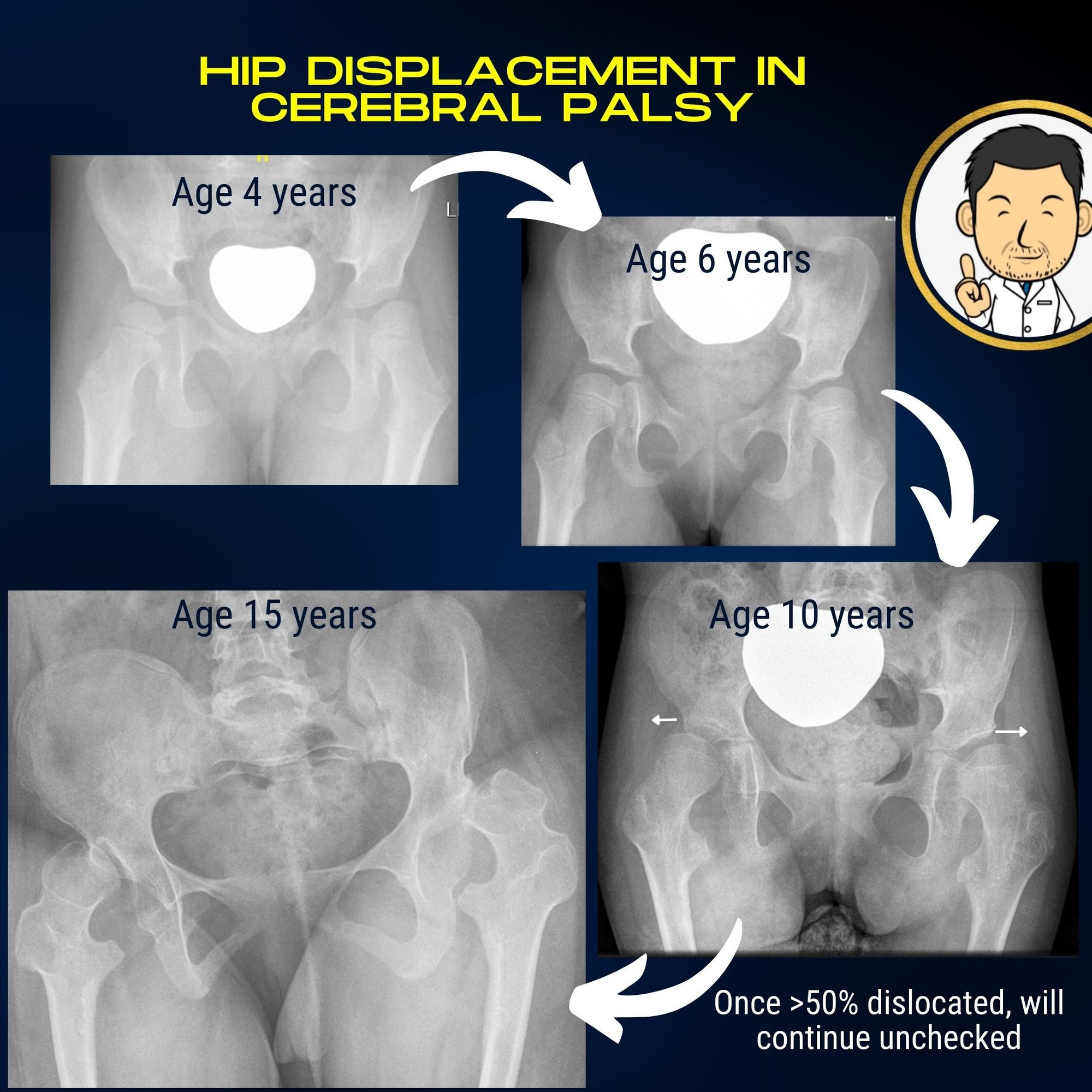

Progressive hip displacement is a real problem in Cerebral Palsy. The probability of this complication occurring is proportional to the severity of impairment in movement and posture. Children with limited walking abillity are at risk of developing hip displacement but the greatest risk is in children who are wheelchair users. In these patients the hips can start to drift out early on in life and over time completely dislocate. The factors which make this occur include weakness of muscles around the hips but also high tone in specific muscles leading to muscle imbalance around the hip joint.

The problem with slow hip displacement over months or indeed years is that it is not often accompanied by noticable discomfort. The child's hips do become progressively less mobile but the progression in stiffness happens gradually over many years. This makes it difficult for care-givers to detect any meaningful change as the slowly encroaching restriction in hip movement takes place in slow motion.

Progressive hip displacement and eventual dislocation leads to several problems:

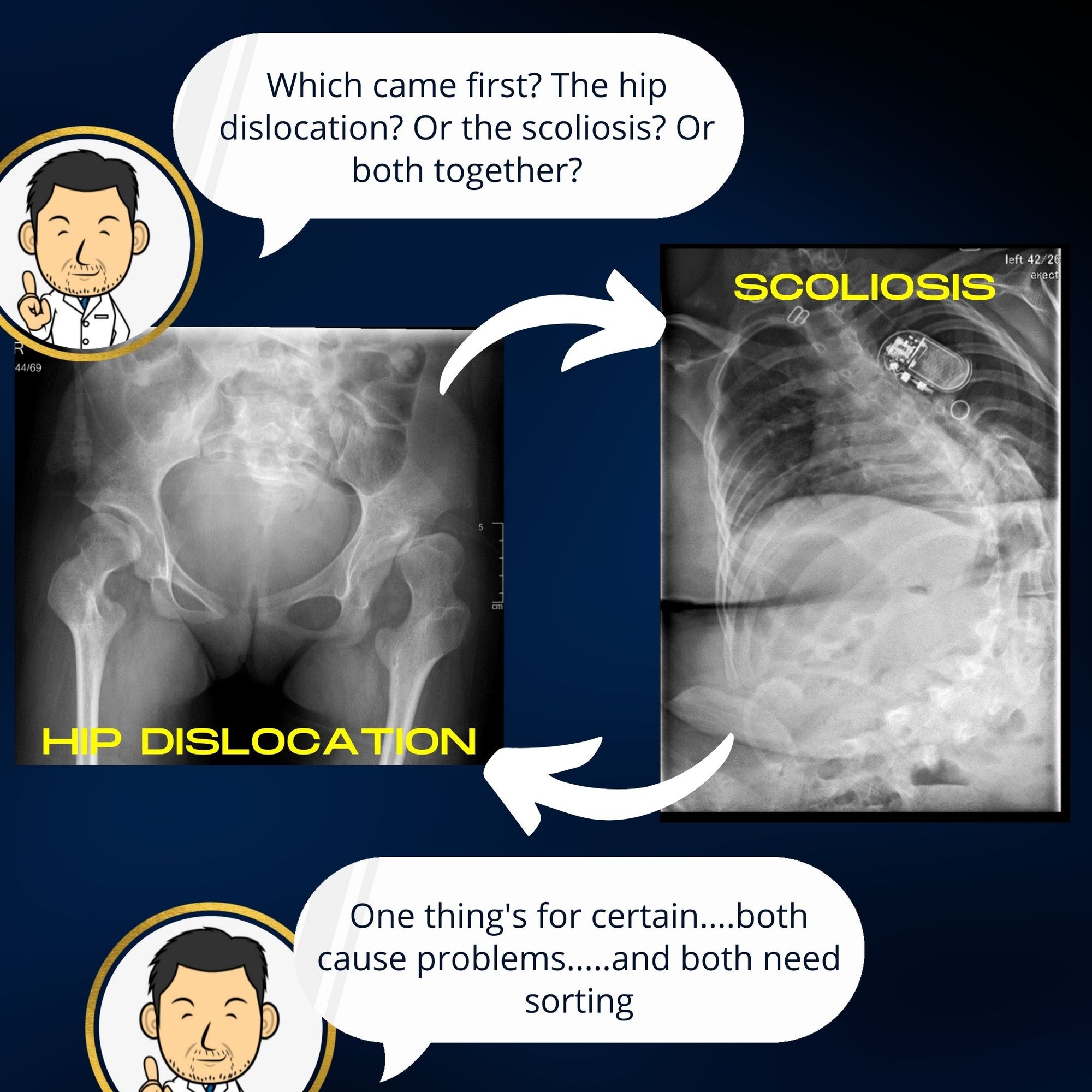

- Altered sitting position - often the hips don't dislocate in a symmetric fashion. Often one dislocates before the other or one hip dislocates while the other remains in. In both cases, the asymmetry in hip alignment distorts sitting posture. The child often can't sit straight in their chair and usually slump to one side. This is not good for general posture, can lead to pressure points developing and has a knock on effect on the spine upstream.

- Scoliosis - the asymmetric sitting posture leads to the pelvis being tilted. To maintain an upright posture, the spine has to compensate by twisting in the opposite direction resulting in scoliosis (abnormal spinal curvature). It is difficult to determine in individual patients whether it is the tilted pelvis which causes the scoliosis or whether the spine deforms first causing the pelvis to tilt. Scoliosis in children with cerebral palsy often gives rise to pain and in severe deformities can affect respiratory capacity.

- Difficulty maintaining hygiene - Progressive hip dislocation usually leads to stiffness in the hips. Washing and dressing can become quite challenging for care-givers and uncomfortable for the patient. In advanced cases, perineal hygiene care after going to the toliet can be very difficult.

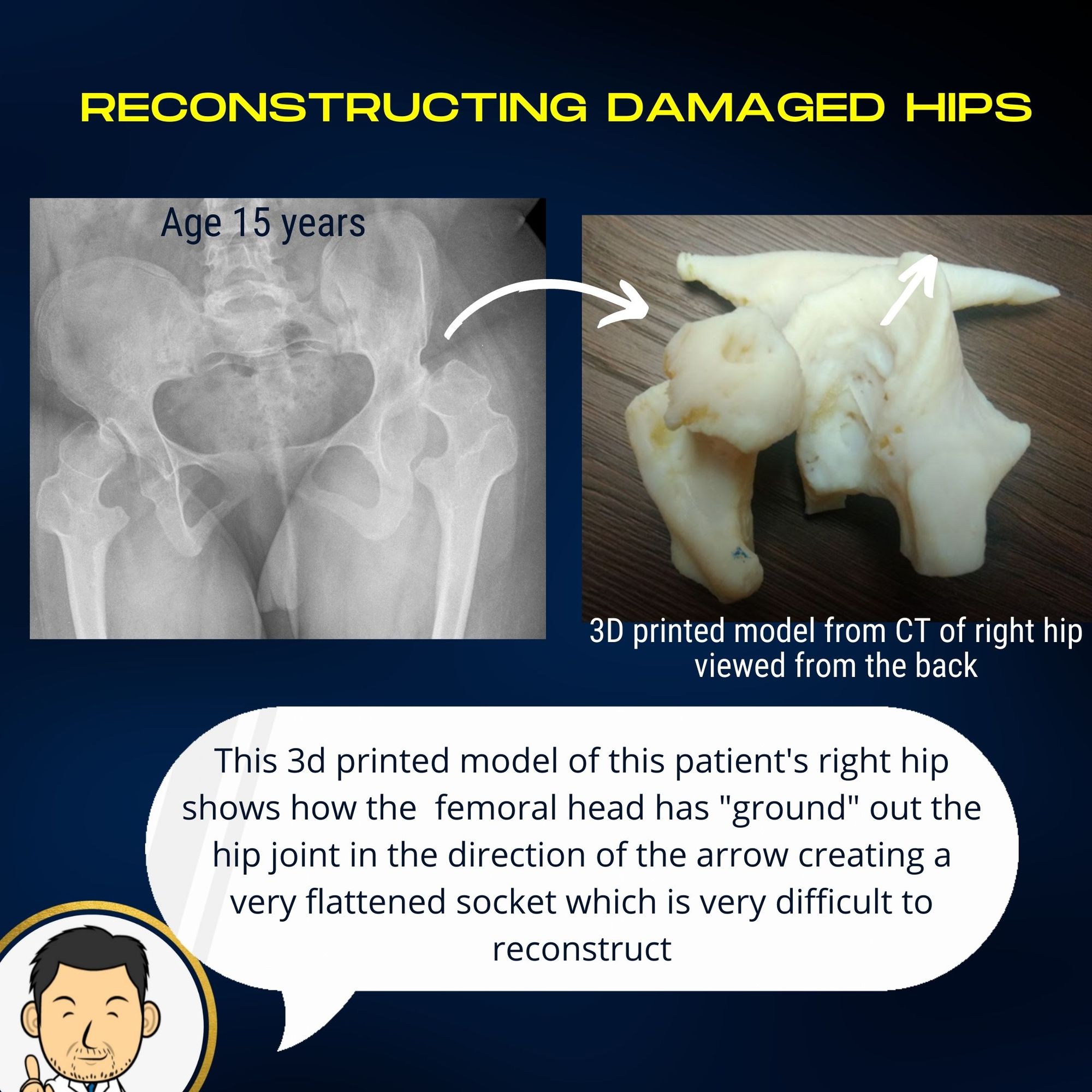

- Painful hip degeneration -eventually dislocated hips become painful. This is often in the teenage years when the hips have become very distorted (due to pressing against the side of the pelvis). In patients with limited communication this often manifests as distress during moving and handling. Often, care-givers have to avoid scenarios where the child remains in one position for a long time due to pain. Long car journeys often require frequent stops. Care-givers and the child's sleep can be disturbed due to the child's position being changed several times a night due to distress.

Unfortunately by the time a child has developed significant symptoms the hips may have been dislocated for some time. Surgery to place the hips back in can be considerably more challenging compared with earlier surgical intervention before the hips became completely dislocated.

We now know that hip dislocation in cerebral palsy and the problems it creates are both inexorable (will definitely occur over time) and predictable (good evidence to suggest that greater than 50% migration on x-ray is predictive of progression towards future dislocation). This predictive insight created the impetus to see if screening children with cerebral palsy for hip displacement could make a difference. Surveillance programmes for children with cerebral palsy have been in place in many Scandinavian Countries for a number of years. Outcomes from these programmes have demonstrated that structured surveillance with clinical assessment and hip x-rays during growth can detect hip dislocation leading to earlier treatment with better outcomes. Indeed, the success of such screening programmes has led to similar national or regional screening programmes being rolled out across many countries.

I am a keen advocate for early intervention in hip dislocation in cerebral palsy for many reasons-

- Early intervention is associated with better clinical outcomes.

- Keeping the hips in can only be good for the spine in minimising deformity developing or progressing here.

- Keeping children comfortable and easy to care for helps both the child and, equally importantly, the care-givers.

- Hip reconstruction where the hips are put back in may not be as successful, or indeed feasible, when they have been out for a long time and degenerated significantly. The earlier they are addressed, the greater the chances of long term success.

- Managing a teenager with cerebral palsy following hip surgery is considerably more challenging for care-givers compared with managing a younger child post-operatively.

- Delaying surgery in these patients means that their deformity can gradually impair their general health which increases the risk of complications in surgery when they are older.

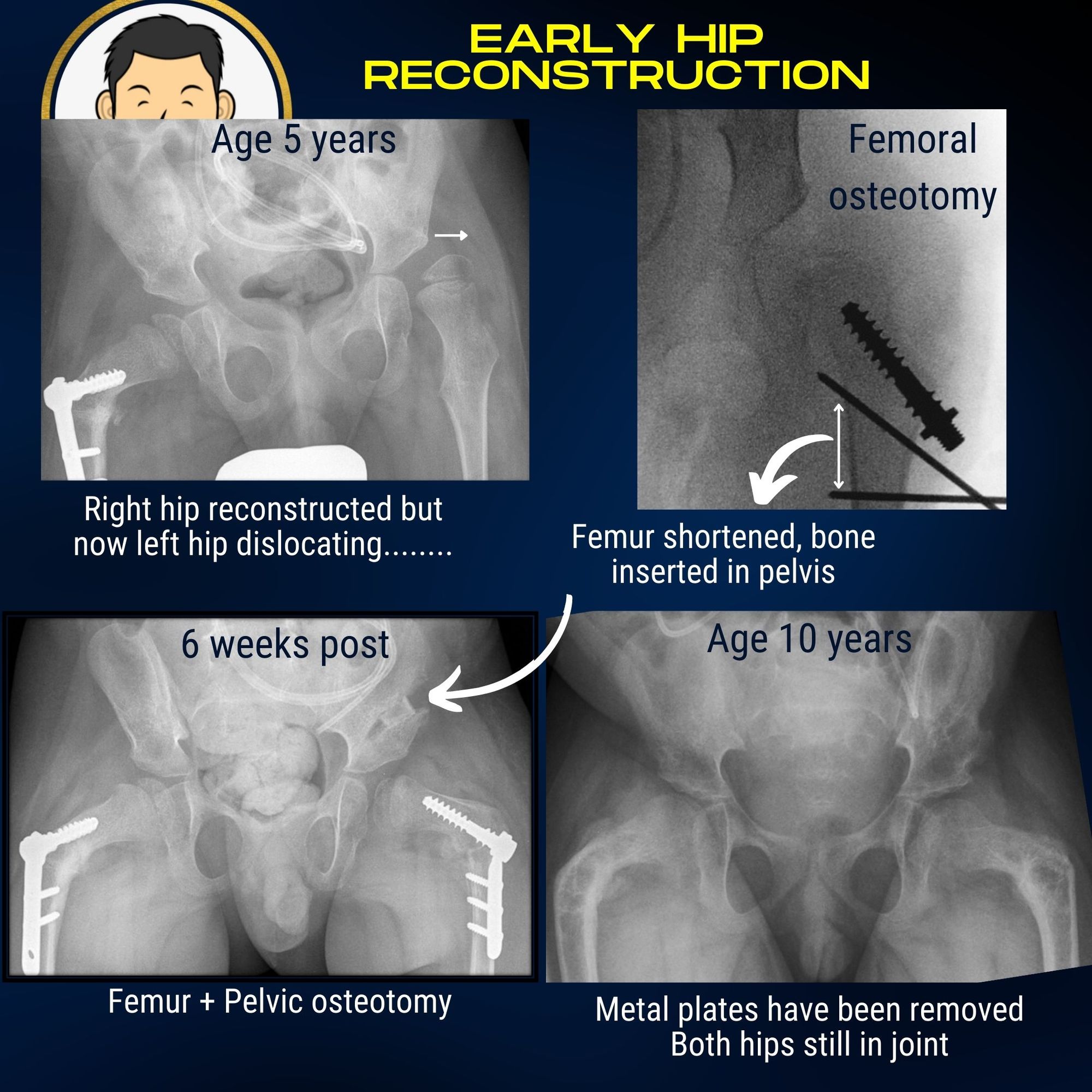

Pre-emptive hip reconstruction in displaced hips

"A stitch in time saves nine" as they say and this is especially true when it comes to progressive hip dislocation in cerebral palsy. Once significant hip migration has occurred (usually evidenced by greater than 50% displacement on serial pelvic radiographs), single stage hip reconstuction remains the gold standard of treatment. If only one hip has dislocated, there is now good evidence to support pre-emptive surgery on the opposite hip at the same sitting to minimise the need for a second operation when the other hip begins to follow suit.

Single stage hip reconstruction is major surgery with all the attendant risks. I refer all patients for "high risk" anaesthetic assessment to ensure that the Team is happy that the surgical risk is acceptable and that if any further inputs are required (e.g. pulmonology, pediatric neurology), that patients are referred before making this decision. Patients are usually observed in Pediatric Intensive Care following surgery until they are physiologically stable for transfer to the ward.

The surgery can be lengthy especially when both hips are being addressed. Peri-operative pain relief and monitoring with urinary catheter, arterial line and epidural also take time to set up whilst the child is under anaesthetic before the operation can begin.

The main steps in the operation are:

- Correcting the deformity in the femur bone - Often the muscle imbalance in cerebral palsy warps the anatomy of the bone pointing the ball out of the socket. Angulation and rotation of the bone need to be corrected by diving the bone and fixing it in a new position with a plate (femoral osteotomy).

- Correcting the muscle imbalance - The muscle imbalance needs to be addressed by "de-powering" muscle groups which have provoked the hip dislocation. The hip adductors are causative and need to be addressed. I detach them from their pubic bone origin so that they can be stretched out. The ilio-psoas muscles is the prime hip flexor and is another deforming force. Shortening the femur when perfoming the femoral osteotomy serves three objectives. (1) The insertion of the ilio-psoas tendon can be excised removing its point of action. (2) Shortening the femur de-tensions all of the surrounding muscles. Muscle-tendon units that were previously short and tight due to contracture are now looser and more flexible limiting the need for extensive tendon releases. As the child grows, muscles will always tighten again so I see this shortening as having an element of "future-proofing"(3) The wedge of bone removed by shortening can be put to good use for the pelvic osteotomy.

- Improving the socket coverage - In cerebral palsy with high tone, the hips dislocate due to abnormal muscle forces across the hip. Consequently many hips don't "slide out". They may "grind out" causing significant deformity in the femoral head but also deforming the socket. Even in cases where the hip has not completely disclocated this effect can be seen with flattening of the socket's curved outer edge. A crucial element of hip reconstruction is to correct this by "bringing down" the socket edge (pelvic osteotomy) to better "capture" the femoral head and prevent future re-dislocation. "Getting the hips in" is important and usually the femoral osteotomy and muscle balancing are sufficient to achieve this. However, "keeping the hips in" assumes equal importance and I think the pelvic osteotomy is crucial to achieve this.

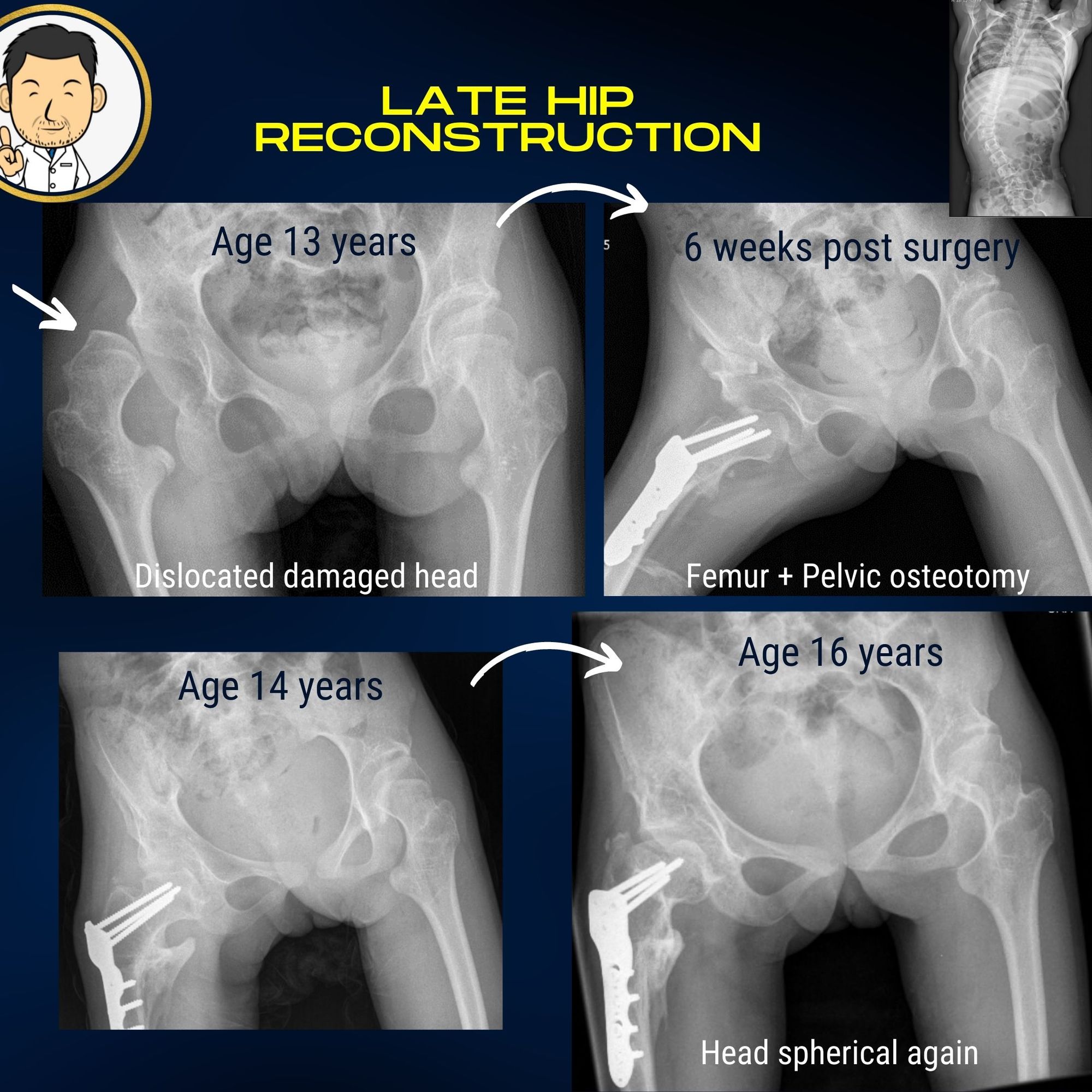

Hip reconstruction in dislocated hips

Hip reconstruction ("putting the hips back in") will always be far preferable to any other type of salvage procedure when it comes to clinical outcomes. Salvage procedures ususally describe procedures where part of the hip is cut out to remove the painful interface between the two bones. Biomechanically, (and perhaps in every sense) removing part of the hip joint can never have an equivalent outcome to putting a hip back in. Therefore, even in long-standing hip dislocations with significant deformity if a hip reconstruction is feasible, it will always be my first treatment choice.

Often care-givers (and myself) will be concerned whether relocating a hip that has been dislocated for some time is feasible before embarking on major surgery. In some cases the judgement can be made on x-ray. However in some instances a CT scan can be very helpful- especially if there is significant deformity of the socket. An exmaination under anaesthetic and arthrogram can also help to determine how easily and satisfactorily the hip reduces into joint.

Hip reconstruction for long standing hip dislocation usually includes the same steps - namely femoral osteotomy, muscle balancing and pelvic osteotomy. However, in most instances these techniques need to be modified based on the severity of the deformity and presence of muscle contractures. Additional procedures may also be required:

- Hamstring release at the knee - this is occasionally required in patients with a characteristic "slouched" position due to fixed hamstring tightness. Usually these are older patients with long standing deformity who are referred because of pressure areas on their upper back from a slouched posture.

- Open reduction of the hip - In long standing dislocations, there can be a contracture of the hip joint capsule and/or bony overgrowth of the ligament traversing the edge of the socket. In these instances, opening the joint becomes mandatory for a successful reduction.