Conditions I treat......... Hip salvage in Cerebral Palsy

I really wish this page didn't exist on my website for all the reasons detailed on the previous page (Conditions I treat.........Hip reconstruction in Cerebral palsy).

Hip reconstruction (keeping/putting the hip in) will always superceed hip salvage procedures (cutting out part of the hip) in every domain you can think of - probability of a successful outcome, overall clinical outcomes, reproducibility of clinical outcome, risk of complications, severity of complications, impairment to quality of life both before and after the procedure, surgical planning, surgeon's stress levels.....the list goes on.

I will always try to reconstruct hips to avoid facing the prospect of salvage. However long standing dislocations are still an issue in most parts of the world. Reluctance to treat (as much if not more on the part of physicians rather than care-givers) or anaesthetic concerns regarding major surgery earlier in life likely all play a part. It is the hope that national surveillance programs, like those first introduced in the Scandinavian nations, will dramatically reduce the number of cases where reconstruction is not possible and salvage is the only option. I have found that in most children where things are not too far gone, reconstruction is usually feasible. There is good evidence to suggest that even with significant femoral head deformity, reconstruction is still the best option. However, young adult patients with longstanding dislocations often demonstrate anatomy that is too severely distorted to allow reconstruction. In such cases, salvage options are the only choice when the patient is in significant pain which can not be managed otherwise.

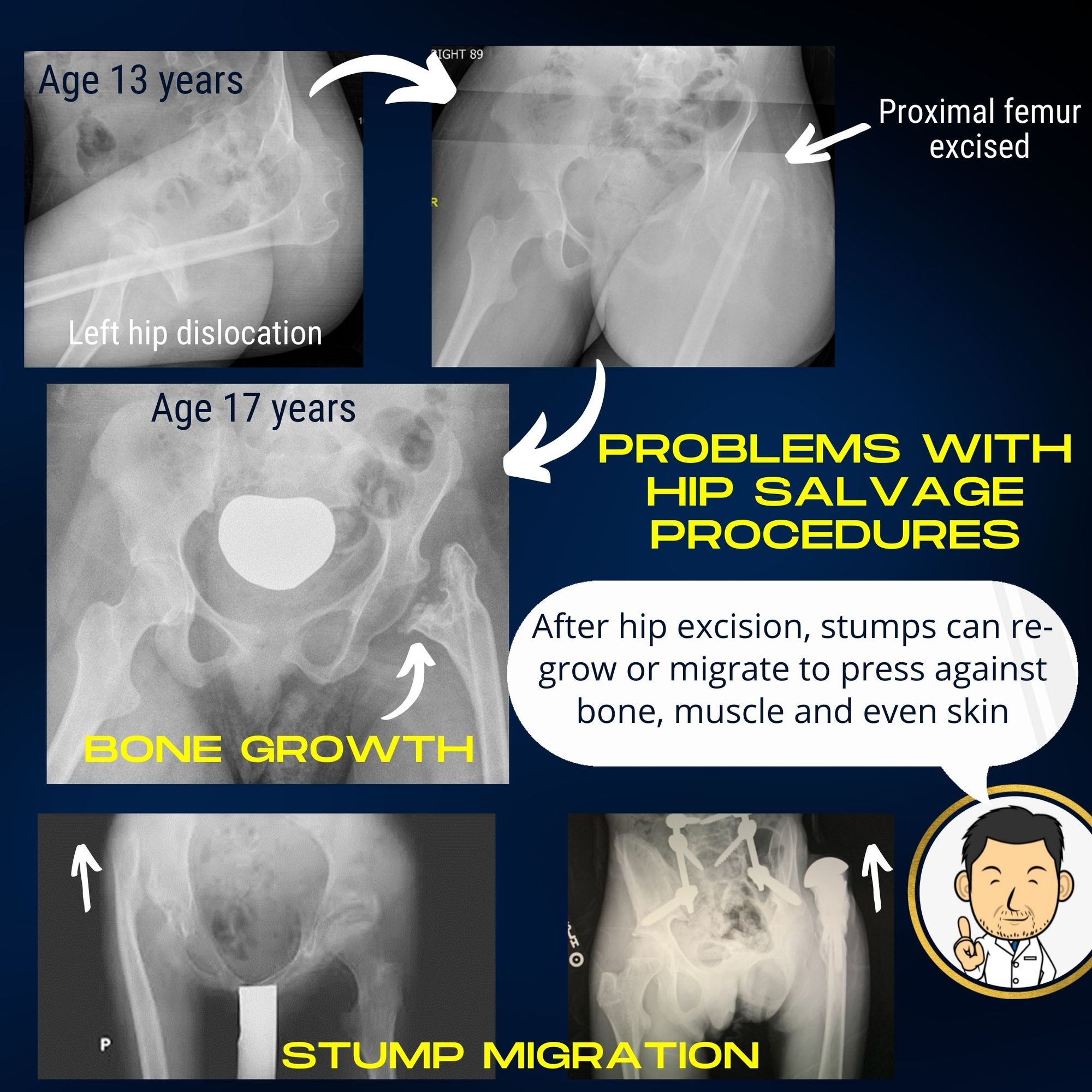

Although many different variants of hip salvage surgery have been decsribed in the literature, what they all share in common is the removal of the femoral head to remove the painful interface between the two bones. Howver, removing the joint in the presence of significant muscle imbalance across the hip due to the high tone can lead to several unfortunate scenarios:

- Over time, high tone in the muscles causes the remaining femur to once again abut against the pelvic bone causing pain

- Over time the femur migrates in the opposite direction and starts to push out against the skin. (At least one published study has reported this happening in the immediate aftermath of salvage surgery where the stump of the femur migrated out of the surgical wound)

- Leakage of bone marrow from the cut end of the femur bone leads to a spike forming. In severe cases, a bone bridge may form between the femur and pelvis fusing the hip in one position. Auto-fusion following hip salvage surgery is a feared complication with very poor outcomes.

In cases where the hip can not be reconstructed due to severe deformity, I utilise two options for salvage surgery:

The McHale osteotomy

In this procedure excision of the femoral head is combined with an osteotomy of the shaft of the femur to angle it away from the hip. The technical goal is to have a larger surface area of the femur abutting the pelvis to give some support.

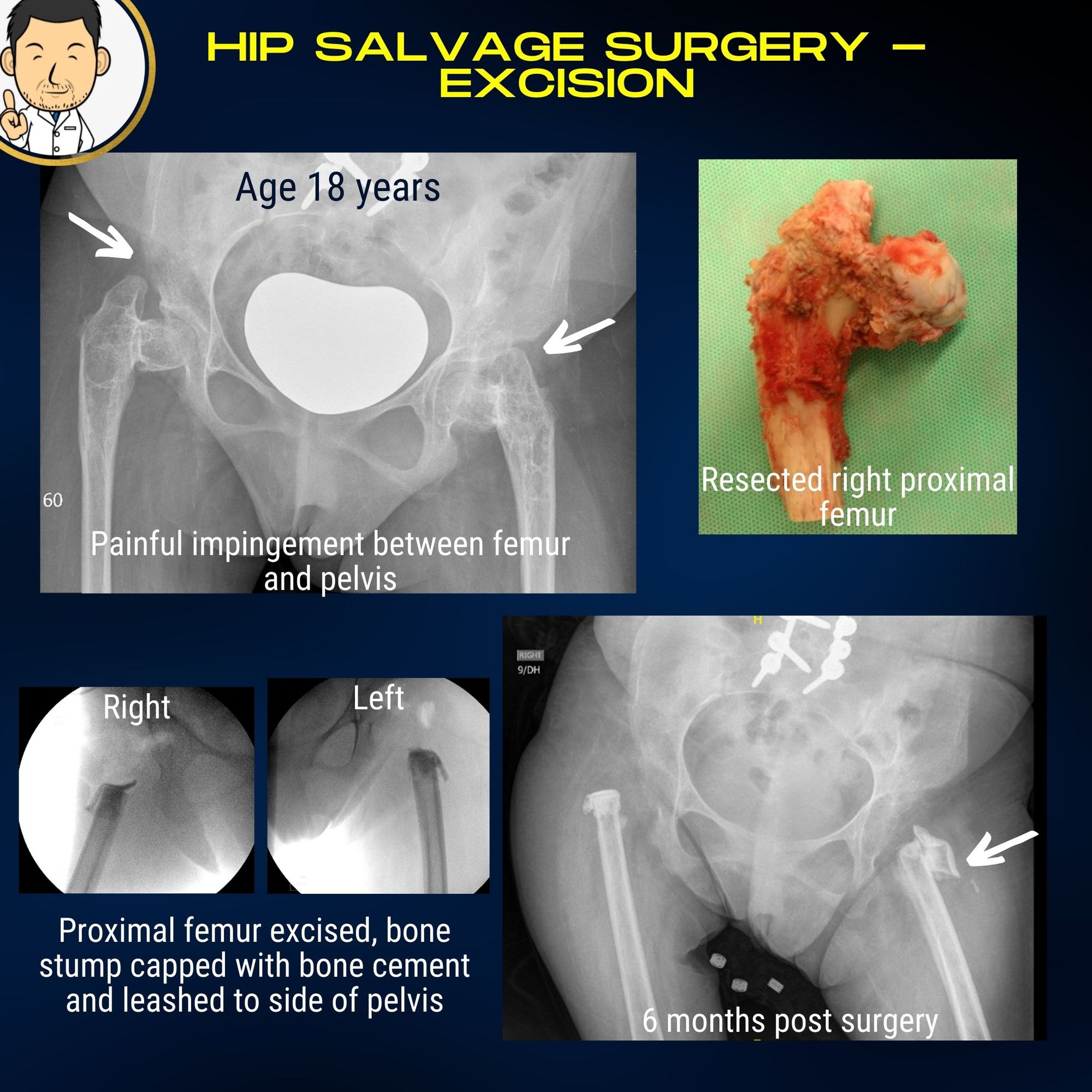

Proximal femoral excision

There are many variants of this procedure described - mainly differing with how much of the proximal femur is removed and what is used to interpose the gap to prevent the femur from coming into contact with the pelvis again. The problem with this procedure is that it does leave the leg effectively flail and floppy. This can make moving and handling difficult. This is the main reason I prefer a McHale osteotomy over this procedure. However in some instances the femoral bone is very narrow and an angulation osteotomy raises concerns about healing and the possibility of a future fracture at the plate end. In such a case, proximal femoral excision may be the only option for lasting pain relief.

To mitigate the problems associated with proximal femoral excision, I have added in the following technical points to the procedure (all helpfully provided by a colleague to whom I owe an immense debt).

- Extensive femoral shortening - I excise a lot of the proximal femur principally to minimise the risk of painful impingement of the stump against the pelvis in the future. Shortening the femur effectively de-tensions the surrouding muscles hopefully negating the effects of high tone in these patients. This does shorten the leg but having a smaller floppy leg when it comes to moving and handling is preferable to a larger floppy leg.

- Taping the femur to the pelvis - Migration of the femoral stump can occur in either direction - back towards the pelvis causing painful impingement or out towards the skin causing irritation and painful pressure points developing. To avoid the latter I use a fibretape loop to secure the femur in the vicinity of the socket so that it doesn't migrate towards the skin (or out of the wound following sugery). Combining this with sufficient shortening hopefully means the femur doesn't impinge against the pelvis in the future or that it doesn't migrate away to cause soft tissue problems.

- Sealing off the cut bone surface - Cutting the femur leaves an exposed bleeding bone surface with potential leakage of marrow contents. This can precipitate new bone formation which can cause a painful spike of bone to develop, or in severe cases, progressively fuse the hip completely. Plugging the bone end with a bone cement plug (bone cement is mainly used to fix hip and knee implants in patients having joint replacement surgery) seems like a good idea to avoid this. Although many described techniques of proximal femoral excision emphasise the importance of muscle interposition in the gap between the two bones, a solid interposition interface to prevent marrow leakage seems desirable.

Following surgery the hope is that all the objectives will have been achieved moving into the future:

- Legs floppy but hip completely mobile with ease of washing and dressing

- Lasting pain relief with no recurrence of impingement between femur and pelvis

- No femoral stump problems causing pressure areas/skin breakdown

- No bone spike formation or hip fusion

Only time can tell if these objectives can be fulfilled in the long term which is why hip reconstruction, if feasible, is still the gold standard treatment when it comes to the best, most reproducible, long term outcomes.